The Empowerment Process Starts

The lake that day was completely frozen over with no hint of the rich dormant life of last summer thriving below the white silence. Mt. Mansfield and Camel’s Hump, my usual orientations to the east, had slipped into the pale yellow whiteness of early morning, and the Adirondack Mountains to the west were lost in a bluish whiteness, not yet knowing that a new day had just barely begun.

I see Astra clearly in my mind’s eye the first day she arrives. A whoosh of cold wind comes in with her as she enters through the door to the outer room. A few snowflakes on her hair create a halo effect from the light behind her. She stomps the snow off her boots, and as she moves out of her own silhouette and into the light of the outer room, I see deep mysterious eyes, a somber look. She would have not gone unnoticed in any room.

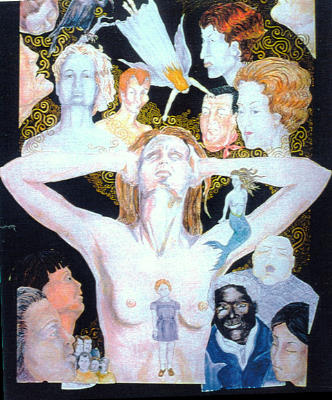

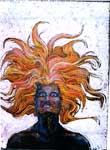

Tall in frame with reddish brown, shoulder length, wild curly hair, she wears an oversized black coat that hangs loosely to her ankles, black woolen slacks, and high, dull black leather boots. ![]() She finds the hot water and herbal tea by herself, but she doesn’t seem to notice the volumes of books and art objects that line the shelves. Maybe she isn’t an avid reader, or maybe she’s too anxious or depressed to look.

She finds the hot water and herbal tea by herself, but she doesn’t seem to notice the volumes of books and art objects that line the shelves. Maybe she isn’t an avid reader, or maybe she’s too anxious or depressed to look. ![]() As we head into the Inner Room, Astra glances at the Athena, Goddess of Wisdom and Knowledge figure, riding a chariot near my chair and plops down in her own chair. We are not total strangers because we have spoken on the phone at length before this visit.

As we head into the Inner Room, Astra glances at the Athena, Goddess of Wisdom and Knowledge figure, riding a chariot near my chair and plops down in her own chair. We are not total strangers because we have spoken on the phone at length before this visit.

Our eyes meet. I start the empowerment process. “Why don’t you just start wherever you’d like to? I may ask you some questions along the way, but I think of this as your journey, your walk. So if it is okay with you, you take me by the hand and I’ll try to see what you are seeing and feeling along the way. As I’ve said, it’s your story. You’re the one who has lived it. You’re the one who knows it best. After an hour or so we’ll take a short break and then continue. Is this okay with you?”

She nods.

“Later, I will go over with you the mechanics of the office. How you can reach me during the daytime and at night. How the lending library works here. What my fees are and if you need any modification in this. How the billing works and things like that.” Astra sits partially slumped in the oversized corduroy lounge rocker. She drops her coat and purse to the right of her.

“Oh, by the way, I’ll be taking notes. They’re your words and my questions that I’m writing down, not my analysis or diagnosis of anything. Just go ahead and start where you’d like.”

I wonder, Who is this woman sitting before me? What does she need from me? What has her life been like? Where is her pain? What is the state of her health? Can she see and hear adequately? Does she feel physically safe? Threatened? What does she say to herself when no one is listening? Whom does she love? Is there anyone out there to love? Does she feel crazy? Does she trust what she thinks? Does she know she has wisdom? Am I the woman who can help her?

The stories she tells are the stories borne by this particular woman. She will tell her stories in her own particular way and in her own time. She will use her own melody, cadences, nuances, and tone. She may tell them in the manner of the original mother tongue of her family or community or ethnic group, or she may not.

As she tells her stories, I may get to learn something about how she goes about her journey, what she packs in her knapsack, or shopping bag, or pocketbook. I will be interested in what survival tools she carries with her, how she fashioned them, and for what purpose.

Nascent images and questions of my own start a beginning mental map as I work with Astra. ![]() Often these maps take on a material form, but for now Astra’s particular map starts with a sketch in brown and gray washes in the manner of the 17th-century Baroque artists, creating dimension with light and dark values as I make a quick study of her unfolding life story. This picture along with my notes creates a rich first map.

Often these maps take on a material form, but for now Astra’s particular map starts with a sketch in brown and gray washes in the manner of the 17th-century Baroque artists, creating dimension with light and dark values as I make a quick study of her unfolding life story. This picture along with my notes creates a rich first map.

I glance over at Athena, knowing I will need her, and we settle in together for the long haul.

“How sad. How sad. There’s just me and money.” She takes another tissue. “So much grief and mourning. When I decided to sell the business, I never expected such a backlash at work. The staff, you know, they need to express their own stuff and their shit and I’m getting it. I haven’t been honest with them, and that feels just rotten.” She runs on. “I’m the youngest of four. I was very sheltered. The message was don’t ever be alone. I was taken to all my parents’ cocktail parties.” She reaches for a generous handful of tissues and readies them in her lap.

She continues to move forward and backward in time: “My parents got old and sick and died penniless. All in the same year, I got divorced, learned to drive a car, and started to live alone. We children were never taken seriously. We were the props in my parents’ lives. It was like a Tennessee Williams play. My parents were hypocrites and bigots. But, then I say to myself, I’m lucky. I have my health, and I don’t have money worries.”

She composes herself, takes back her first voice and starts again. “I feel I am cracking under the pressure now. I have so little time outside of work and I’m reacting negatively all the time to everything. What do I want now? I don’t know. I think there’s no way out. It’s terrible. I feel just terrible.” The woman sobs. “There’s no respect for what I do now at work. The business went from zero money to a great deal of money. I feel it’s a cruel trick because there’s no one to enjoy it with. Just think of the joy I could feel.” Her voice trails off. She wipes her now reddened and moist nose.

I lose her for a while as she silently roams around somewhere in her own unmapped territory.

Then she pushes on with her story. “I believed in my business. It was my baby, but I was not naive. My business wasn’t about money itself, but it definitely was about financial security. I thought, who will take care of me if I am sick or old? I saw the business as a gamble. The payoff would be eventually selling it. Like now. Now, that’s the big thing that’s come up for me: selling my business. We sold the business.”

Slipping into another thought, she adds, “Did I tell you yet that my mother called me ‘googly eyes’ when I was a child?” She heaves a deep sigh. “I need to sleep. If only I could sleep. I just can’t sleep. Everything goes back to my sleep.”

Next to my mental wash of tonal values, a side list of follow-up ideas has begun: “Support system? Sleep deprivation? Time off? Medical workup? Frequency of visits?” For now, I continue to let Astra lead but allow my list of questions to grow.

The challenges of the young child continue to mingle with the needs of the adult woman narrator. “We lived in New Jersey, and we always lived near the ocean.”

So that is what I was picking up: the ocean.

“I love to be near the ocean. We lived in big expensive houses, but they were always rented. We never owned our own, so we moved every year or two. I went to private schools. In one school—it was junior high—I was kicked out because of my behavior. It was terrible because it was the only school I was at for three consecutive years. My parents sent me to Florida for a while to live with an aunt, and then in the middle of the year, I was sent to a school in New York City, and I really learned there. It was a tutoring school. But,” she slows down, “some things happened there I didn’t like...”

Again, her thoughts drift off somewhere. She comes back, “Believe it or not, I didn’t go to high school like everyone else. Then I wanted to go to the Parsons Institute. My mother and sister had gone there, but I was sent to a women’s college in Rhode Island. Then the family ran out of money, and my mother said, ‘You have to go to Katherine Gibbs Secretarial School.’ So I went. You know, it just never occurred to me that I could borrow the money for college.”

“I’ve certainly heard that one in here before,” was my response.

“My home had the feeling of being...” She is rolling some choices around in her mouth again. “...formal and old. I always felt different. I was the youngest, so I spent a lot of time alone as a child, and when I was in fourth or fifth grade, we lived out in the country. There was no one around to play with. I can remember growing up and how my friends’ parents were and how they talked to them and they knew the latest hip language, and they knew what was going on. It was like stepping into another world.”

“Did I tell you yet that my mother called me her little pocketbook? She took me everywhere with her. I always had to go to these parties with my parents. I got to know a lot of basements. I would sit and think and make things up in my head. Hah! I saw a lot of night life in New York in the fifties: Club Twenty-One, The Stork Club, Luchow’s Restaurant.”

In the middle of her childhood story, I suddenly have a flashback, a merging of politics and music from my own youthful days in Greenwich Village. Luchow’s, an old-world German restaurant requiring reservations, contrasts with my own working-class experiences in New York in the fifties. It is summer.

In the middle of her childhood story, I suddenly have a flashback, a merging of politics and music from my own youthful days in Greenwich Village. Luchow’s, an old-world German restaurant requiring reservations, contrasts with my own working-class experiences in New York in the fifties. It is summer. ![]() A New Yorker by birth, I sing with the crowd at a large fountain in Washington Square Park as the young Pete Seeger plays his guitar and sings, head high, body proud,

A New Yorker by birth, I sing with the crowd at a large fountain in Washington Square Park as the young Pete Seeger plays his guitar and sings, head high, body proud,

“Oh, you can’t harm me, I’m stickin’ with the union.

I’m stickin’ with the union ’til the day I die.”

![]() Then I hear Marion Anderson’s rich, black, contralto voice in the warm night air, uptown at Lewisohn Stadium, singing, “He’s got the whole world in His hands, He’s got the whole wide world in His hands.”

Then I hear Marion Anderson’s rich, black, contralto voice in the warm night air, uptown at Lewisohn Stadium, singing, “He’s got the whole world in His hands, He’s got the whole wide world in His hands.”

Astra’s cello voice interrupts my own altered state of consciousness. “I also had these huge temper tantrums. We moved every one or two years. I knew my age by the house we lived in. Did I tell you I knew I was a mistake? That’s what I heard in the family. I wasn’t planned, wasn’t wanted.

I am compelled now to respond to the child’s pain. “You must have felt very helpless at such a young age trying to soothe your mother’s pain.” She whimpers and nods, but she will not be diverted from the memory of her father.

She moves on quickly, unable to bear the scene. “In that house there were intercoms, the old-fashioned ones where you blow into them. So we’d be listening on the intercom to hear all of this going on. One of the classic memories all four of us recall is of my sister, my two brothers, and me sitting on the stairs listening to the stuff going on below. You know, now that I think about it—I always heard it, but never saw the actual scene. At least, I think that’s true.”

I jump in now, continuing the empowerment, “But this time you came here instead. You didn’t overdose. You’re trying another way. Is that right?”

“I hadn’t thought of it that way. Yes.”

“Can we back up a minute? Did I hear you say you split your head open?”

“Yes.”

“What happened to you?”

Astra has a seizure disorder! I must now rethink everything she has told me, through the eyes of a child growing up not only with an abusive father, but with the burden of a seizure disorder as well. I understand now that she has the special knowledge of a child who has experienced other states of consciousness. I make another side note: Get medical problem list. Her words and images are freed up now from their cellular prison. She breathes more easily.

“You’ve been waiting a long time to tell this story, haven’t you? I’m sorry you’re experiencing so much pain.”

She nods and sobs uncontrollably. I wait, respecting her emotional space.

Then, leaning forward to create less physical space between us, I say, “Do you think you can live on my faith for a while? Can you let me carry some of this with you?”

I don’t remember now if we ever took a break during the two hours that winter afternoon. My notes show no break after the first hour as we had planned, just a blank section probably where we dropped through ordinary time. I have a vague memory of the movement of the low winter sun in the south window on my left to the west window and the pale blue-purple lake behind her. And I remember her overwhelming sadness, her plaintive wail, and the “Elegy.” Neither of us would have guessed that cold January day, when everything seemed so frozen in time, that we would be working together through fourteen seasons, the thaw of three new springs, and many lake walks. I only know that my mechanical timer, which I had set for two hours, brought us back to the requirements of ordinary time.

Creating a Joint Narrative

It is already spring. On my lake walk today, the lake is wild and swollen like a woman before she menstruates. The trunks of the large elm trees sitting now in the high frigid water of early spring are full with the lake’s wetness. Large gray logs and driftwood from another shoreline sit on our upper banks now. A dark green wave throws itself amidst three logs on the shore and sings its way back to the lake with a slow gulp...gulp...gulp...gulp. At regular intervals the hypnotic sound repeats itself. The swollen spring lake today reminds me that nothing is frozen in time forever.

I especially listen for those early knowings that are not subject to appeal or repeal by the rational mind, or any other amendments that inform. These original childhood knowings remain markers through the long days and nights while all other markers fail. That they may keep the rest of the ocean of knowing in darkness does not matter; they exist by virtue of their early snaillike attachment to us. Some of these early knowings are the constructs of the child’s mind—created as protection from some perceived or real evil. At some point their power to direct our lives must be examined.

Our plan to see each other twice a week is a good one. In the interim, at my suggestion, Astra has seen a physician regarding her sleeplessness. He prescribes medications, and they don’t work. She has warned me that she has idiosyncratic reactions to drugs, and, knowing her body better than anyone else, of course, she is correct. She has decided to take no medications, and her sleep has improved. The urgency and desperate feelings of her first visit have lessened somewhat.

We hug comfortably now as women friends do, and she sits down quickly, eager to continue where she left off after the last session. She drops a new lighter-colored ski jacket on the floor in its usual place. Like her jacket, her mood is lighter, more relaxed.

“I want you to know that I’m feeling some relief now, that there is someone here to help me.”

“I’m really glad to hear that I can be of some comfort to you. I believe that there isn’t anything two women can’t solve if we put our good minds to it! It’s on the basis of this belief that all of our work is constructed.” We smile together, sharing this two-woman secret.

At this point in our work together, I lay another mental map over my earlier ink wash. It takes on a different look. I am now the busy surveyor, placing colored markers on Astra’s topography as I listen for critical nuclei of learnings. I am beginning to orient myself to the map of her idiosyncratic life space.

Our joint narrative expands her life story, and other newly remembered stories have a larger space for expression and mapping.

Reliving a Childhood

Today Astra comes into the session more relaxed and spontaneous, with questions of her own.

“I’ve been on a childhood trip of sorts. I got out some of my old journals this past week, and I’ve been reading them. In times of crisis, I don’t write—like when my mother and father died,” she begins. Then she adds, “But now I can. Do you keep any journals?” she asks me.

I take the invitation. “It’s funny you should ask that because I am reading Anais Nin’s diaries and essays. In the introduction, she explains that her diaries and her later writing are like two communicating vessels, and that her diaries feed her later work. To answer your question, I use my journal writing as a way to nurture my mind and spirit. I think more in terms of patterns and clusters of ideas. I paste in symbols and images, things I don’t yet know the meaning of, but things I am drawn to. I add religious symbols from different cultures: Tibetan prayer wheels, Buddhist prayer flags, rosary beads, mezuzahs, hamsas, things like that. I think I’ve created my own missal of sorts. If you like, someday I’ll share some of them with you as we work together.”

“Well, that’s interesting. I’ve done a lot of writing in mine over the years. I have volumes of notes and drawings.”

“Maybe you wanted a shorter answer from me,” I say, testing my contribution.

“No. I was really interested in what you said. I was thinking as I looked over my journals, have I ever been happy for any sustained period of my life? I don’t think so. I have to endeavor to work really hard to make the glass half full. I’m beginning to wonder if I use pain as a way of measuring my strength?” She pauses reflectively. “I think my nature is to be a basically happy person, but you see, I think my nurture didn’t celebrate it.” Then dismissing herself much too quickly in a cute little child’s voice, she adds, “Ah, well, ah well, that’s me.”

What is it that Astra does here? She seems to negate her own serious thoughts with a trite voice that says, “I’m here, but don’t pay attention to me.”

Then with that high-pitched voice, cute smile, and a big shrug of her shoulders, she says, “Ah well, there it is, that’s me.” This is not the cold, agitato, intruder voice of the first visit, but the other one again, that trivializes and almost negates the seriousness of what she has just said to me.

I decide to confront her. “What is it that you do with your voice here? It seems that often when you are talking intelligently and seriously about your own needs, you shift to this voice that cancels out or negates what you have just said.”

She begins crying. "I knew you would say that.”

“Please know that I’m not judging you, but I want to support your own needs and intelligence. We need to understand this voice, when and where it was born. Getting back to your goals, I think they are reasonable and wise.”

She hurries on with her own narrative. “I was like the doll in lots of people’s eyes. My mother used to call me her little pocketbook because she would take me everywhere with her, and to this day, I am not exactly sure why that was. The term bothers me.” She looks to me now for new data.

“What do you think about this?” she asks.

“Well, let me think. My first reaction is that a pocketbook is an object. It has no voice. It has no movement of its own. It sounds a lot like the way you felt as a child. Not listened to. Not noticed. No voice, just an object that was taken places. But I understand that your mother had at least one good reason for keeping you close by: your safety.

“I’d like to learn more from you about how this bright and gifted child sustained herself. Did you feel you had a voice as a child?”

“Well, I did. I had more power over my parents than the rest.”

“Really? How did you use this power?” I ask Astra.

“In about fourth grade, I started intervening in my parents’ fights. First, I started writing notes. One night I put a note on my father’s desk. ‘Stop treating my mother this way or I’ll never speak to you again.’ Then, I actually physically intervened. I would just push them apart. That’s what I did.”

“Were you able to stop them?”

“Yes, they would actually stop fighting.”

“You know, even though you felt some power in that situation, parents are the ones who are supposed to monitor and help us to know what is appropriate behavior and to help us to know how to handle strong and difficult feelings. From what you’ve described, in your home you were trying to do the parenting part. The roles were reversed in your family, and your sister often had to parent and protect you. This is a big burden for someone just six years older than you.”

This new information I hope will help Astra reexamine and rename her experience. I continue with my teaching.

“All children have to learn what their place is in the family structure. As you’ve noted now over and over again, you were being asked to accommodate very frequently: moving often, keeping yourself level in your parents’ tumultuous marriage, trying to protect your mother, finding a zone of comfort from which you could function with periods of some reprieve and peacefulness. Lots of activity for a young child.

“You got the idea as a young child that love was conditional. You didn’t have much opportunity to develop your own uniqueness and strengths, or to have your specialness validated. Your primary task was surviving emotionally as best you could. Your developing interests and needs were secondary. A kind of compromised person developed, ‘a persona,’ as the Greeks called it, a mask that’s worn. This has been at a great cost. You certainly tried to test yourself out, support your mother, challenge your father, fit in at all of these schools. The compromised child comes out of pain. What about a voice for yourself? Where was it?”

She begins crying. “I didn’t have a voice for myself. I never felt encouraged about anything.”

“So, to get your child needs met, you had to go into battle. You must have experienced terrible anxiety and helplessness.”

“Well, not exactly. I felt some power.”

“I understand that you felt some power in the situation you just described. Any young child would have had a rough time adjusting to so many changes of houses, schools, teachers, and peers. A child needs to feel that her basic needs have been met, to feel safe and secure, that her parents will be there to feed her, protect her, care for her with some consistency. The child needs to feel that her own body has been attended to, the basic rhythm of her own body noted—going to bed at a reasonable hour, for example. The child needs to feel listened to. Developmentally, your needs were not met, and your seizure disorder gave you a tremendous burden to handle at such a young age.”

“Well, I don’t know what’s normal,” she tells me pensively.

That one line of Astra’s, “I don’t know what’s normal,” carries much emotional weight, for it reflects the lack of information, both in terms of basic knowledge and the ability to deal with strong emotions, that many children from alcoholic homes have. What is reasonable? What am I entitled to? How do I do this? “I understand. That’s what I’m trying to help you with here. I’m giving you new information. What’s okay? What’s reasonable to ask for?”

“Well, there were two levels of culture in my house, the parents and the children. We were the props. We lived on witty sarcasm, you know. Can you pass the acid test? Can you take the sarcasm? There was scapegoating and cruelty, and the trick was to see if you had the ability to hide your pain. Nobody was ever real.”

“How did you feel toward your father?” I ask.

“As a very young child, I knew he truly cared for me. You see, this was before I knew about his violence. At the time, his drinking wasn’t in my awareness. My recollections of my father were of him scooping me up or putting his face close to mine and saying, ‘You’re so cute I could eat you up with a spoon.’

“I remember there is a family story that was retold often when I was very young. My mother had to leave because of illness in her family. The story is that when she left, I was crawling, and when she came back, I was standing up. I understood this story to be a special family story and a special experience for my father.”

“And for the young child hearing it repeated. Am I right?”

“Yes.” She sighs. “But sometimes it’s so confusing.”

The core emotions of fear, hurt, anger, sadness, and loneliness of a young child in an abusive home are slowly becoming evident. But this strong willed, dispirited child has tried to break the rules of silence of most such homes. She questions her mother for answers and challenges her father about the unfairness of it all.

***************

It is summer now. The south window is open. Someone is using a power mower under our windowsill, and our conversation is brought to a sudden halt. So much for the peace and quiet of a therapist’s office! We sit quietly and wait to regain our work space. Finally, the noise fades and Astra begins.

She begins crying. “I tried to be the brave, smart, funny, grown-up little girl to get their attention. The only time I could be authentic was when I was alone. I could never be authentic with consistency and acceptance. I have a lot of evidence in my life that I am not worthy of love. I thought I just wasn’t quick enough, that I was stupid. I tried to get even with a temper tantrum. They ignored me. I just wasn’t important enough. My family agenda was more important than going to school, like playing Scrabble with my mother on my school lunch hour. Can you imagine this? That always came first.”

The named and unnamed fears sit beside us now. The helplessness and hopelessness of the young child are evident. I make a decision to find out what other roles she played in this alcoholic family. What else did she actually do to lessen the tension in her chaotic household? Children in alcoholic homes often play out different scripts over and over again to reduce family tensions. But for now I stay with the emotions of the moment, to find out what this child did to deal with her pain.

"Astra, where did you hide yourself as a child? Did you pray? Did you speak to God? Do you remember what you did to sustain or soothe yourself? Did you have any special words or prayers that you repeated over and over? I am searching for how you, this sensitive and frightened child, responded to such pain and confusion. Do you know?"

There is a clear qualitative shift in her attention now as she looks beyond me. She has a glazed look in her eyes as she describes a scene from her childhood: “Yes. I was about 8. I remember I was alone ice skating. There was this large frozen stream with large bends in it, first left and then right. It was dark and mysterious. The pine tree boughs were bent low and frozen over right into the stream. It was very quiet and beautiful. Then, as I went around the last bend to the right, I suddenly saw a huge lake with many people, dazzling colors, and sunlight. It was a wonderful feeling of being in nature—a connectedness with beauty—a whole and peaceful feeling.”

Just at that very moment, sharp edged shadows created by the afternoon light become soft and subtle as the sun sets behind her. We both slip together again from ordinary time into Dream Time. We sit for a few silent moments bathed in the golden rays of a summer setting sun and the peaceful, unitive experience of a happy childhood memory. So I understand this is one way in which the child survived.

“That was such a beautiful place you brought me to,” I tell her. “I don’t know what you would have done if you weren’t such a gifted and imaginative child. You were a child who tried to protect a dream somewhere, to keep it safe. It’s as if you made a compact with your higher self to retain this sense of awe and wonder.”

“She listens, then wistfully and tearfully, she nods. “Beauty. I feel I’ve lost that. I think that’s why my home is so important to me. It’s a sanctuary, a place I don’t have to play a role. Do you understand this?”

“Yes, I do.”

We sit in the silence of Beauty appreciated now. I continue, “Can we go back to something that you said before about a period of your life being over and that you equate this time as similar to the time around your divorce? So in a real and some symbolic way, as well, the two periods have some things in common?”

“Yes, but I’m not sure what...”

I am curious and would explore this with her, but she moves on in to the landscape of her own map and needs.

“Do you know that I went to first grade in one school, second grade in another, third grade in another? I stayed back in fourth grade because I was sick a lot. Sixth grade in another school. Seventh, eighth and ninth, one school. Tenth, two different schools. Eleventh and twelfth, believe it or not, I did in one year at one school.”

“What happened to fifth grade?”

“I can’t remember. There’s so much I don’t remember.”

“How do you know this?” I ask her.

“Well um … because I feel these…” she swishes a bunch of words around in her mouth again, “…large holes of silence in me, that feel so awful.” Large heaves of sobs.

“Well, we may not have the words for all of these silences yet, but at least we have an image for them—a large hole. Can you tell me what you did as a child to adjust to all of these changes as a result of those frequent moves? How did you handle it? What did you do to fit in? This was an enormous burden for such a young child. And then I wonder too about your adolescent years. You were dealing with so much.”

Astra remembers. In the biological process of remembering, the one hundred billion or more nerve cells with their minute dendrites and axons in the brain respond to at least ten different volumes of sound produced by strong emotions. (Any musician knows there are more than ten, and any mother trying to get her child indoors for a bath and bed on a summer evening knows the volumes of sounds she needs to accomplish this task.) These messages are sent through neurotransmitters. Remarkably, the same cell firing can occur from that which is remembered without actually seeing. The brain stores and recalls these shorthand notations, called neurosignatures.

The fidgetiness and fear of the young female child is evident now as a memory sends Astra’s whole body into alert mode. Her dark brown eyes widen. Her pupils enlarge. The skin across her cheekbones is taut. Her inspirations and expirations are syncopated. Her body informs me and accompanies her words.

“By changing schools so often, I got into a whole routine of establishing myself with every new set of classmates. I had to figure out how I was going to fit in. And that took the shape of primarily deciding what I was going to be in this particular class with this particular set of people. I could be the artist, the writer, and the comic. I would observe the group and see what the competition was, or where I could fit in. And so, if there was one kid in the class who was the acknowledged artist, I might back off and be a reader or a writer because these kids had all gone through school together. Do you know what I mean?”

“Yes, so you did a lot of disciplined scanning and assessing where you could fit in that would not upset the balance of your peer group that was already established. Not threaten anyone. So you were constantly accommodating to others. Finding a place for yourself. Not an activity that you might be interested in or would have preferred, but what you thought could get you accepted into a new group?”

“Yes, that’s it, over and over again. That’s what I did.”

“You know, another child in your situation might have given up. It requires fortitude and intelligence to do this. Do you have any memories of who did nurture you in your childhood? Was there anyone else, any other adult, who loved you in your house? You must have drawn from whatever strengths you could muster up.”

She knows immediately. Her face is animated now. Happy. Anticipatory. “Yes, the black maids. There was a string of them. I remember especially our black maid, Liza. Liza was the one with the black dress and white apron. She was large, so warm, enveloping. She was older, with white hair and spectacles. She was very much a mother figure to me. Now Julia, the other maid, only came in the summer.” Her eyes widen. “She made the best iced tea on earth. I would stand there at the table and watch her. It had just the right amount of everything. It was and is the most perfect tea I have ever had.”

“You know, I can almost taste Julia’s tea.”

In that happy moment, the young child, parched for lack of understanding and attention, is transformed through a summer tea into the loved, happy child of summer. As is true for many other middle-class white women I have worked with, the task of earthly love and nurturing is placed on the shoulders of poor black women. A more stabilizing and nurturing kitchen story sits side by side with the earlier violent one.

“It’s funny ... no one has ever asked me that question.”

“What question?”

“About who else might have nurtured me, who else was there.”

“Well, the origins of it come from a childhood experience of my own, and from my work here.” I tell Astra. “I want you to know that under my pale skin is a black soul. That soul started being born on a train headed south with my parents. I want to tell you a story.”

“Well, the origins of it come from a childhood experience of my own, and from my work here.” I tell Astra. “I want you to know that under my pale skin is a black soul. That soul started being born on a train headed south with my parents. I want to tell you a story.”

I now drop myself into another state of consciousness: “When I was about 8 years old, my father’s mother gave us money so that we could take a two-week family trip to Florida. We went by train, and the trip took twenty-five hours. That trip was one of the most significant events of my early childhood. I was glued to the window seat. My eyes hungered for the excitement of anything I could learn or see from the train window. My parents could barely get me away long enough to eat the sandwiches they had brought.

“The train left Grand Central Station and went from the dark of the terminal and its long tunnel into the bright light of the day. For a long while, I saw apartment houses not much different from the one I lived in, although higher, more crowded, and in much worse condition. I noticed that the people were all black. I noticed there were no whites anywhere, not in the street or the stores or the houses. It was a simple observation.

“Soon the landscape changed, and my eyes took in many country sights unfamiliar to me... miles and miles of trees, dirt roads, rural homes. No more crowds of people, but people walking alone, in twos or threes, appearing to move more slowly. For the first time, from my train window, I was experiencing what the world was like outside of the life and movement of Greenwich Village and metropolitan New York City.

“I delighted in learning the names of states I had never heard of before and noting them in my new diary. As we headed into the late afternoon and night, I began to notice fewer white faces and more black faces, and then, as in a film in which the picture frames move more slowly and one notices with greater intensity, no white faces at all.

“As I watched minute after minute, a slow but very deep understanding came over me. All I was seeing were black people. All the black people were living close together. All of their homes were small and poor. Many children wore no shoes. As I looked into their homes, I realized the walls of the homes were covered with newspapers. Their houses were dimly lit, but I could see the same sparseness in each home—a table, some chairs and mattresses and some beds. Suddenly, I understood—with that mode of knowing before culture corrupts the innocence and perception of a child’s mind, when she is open to seeing things just as they are. The black people in my city and the black people in the country were all kept together! White people did not live among them! They were all very poor. Since the black people seemed very much poorer than the white people I knew, then the white people must have done this to the black people somehow! And I knew in the pit of my stomach, it was all wrong!

“Coming from a working-class family, I understood what living under crowded conditions was like. But that day I saw what real poverty, real sadness, real deprivation were like. Before we reached Florida, I understood something I had no words for: racism.

“When I heard someone in front of me whisper, ‘We are now passing the Mason Dixon line, and this is Jim Crow country,’ I did not make the connection between those statements and what I had just learned without any teacher. The train ride was the teacher.

“Before we reached Florida, and before I had any college-level courses in sociology or economics, I had seen and responded to someone else’s oppression and activated a deep sense of compassion within me. This event was one of the earliest constructs on which my views about the world and my core body of knowledge were built.” I sigh, remembering this childhood awareness.

She nods from a place of her own wisdom.

We sit for a while in the silence of oppressions, and our session ends.

*****************

September has always been a melancholy month for me and now even more so. September is the month of my birth, the time of the High Holy Days, and the month of my wedding anniversary. This September, after a chaotic scene in an otherwise quiet, but too rational and controlled household, my marriage of thirty years blows up. I must live alone and face my own personal crisis.

Since Astra and my oldest daughter have somehow met and become close friends, I don’t know what the two women may have shared about me. I am deeply concerned that Astra will pick up my own undulating emotions and ensuing body sensations, since at this juncture in her own healing, she is sensitive to and intuitive of my thoughts and moods. If I allow myself to feel my own pain, as we work, I will be pulled under. ![]() As I struggle with these feelings, I think about how Virginia Woolf might have felt when she filled her pockets with stones and headed out in the River Ouse, hoping for a quick and strong undertow. When I feel somewhat stabilized and my pain is lessened, I decide to tell Astra in a few sentences about my current situation, believing that my own life experiences can enlarge her repertoire of possible narratives from which she can draw.

As I struggle with these feelings, I think about how Virginia Woolf might have felt when she filled her pockets with stones and headed out in the River Ouse, hoping for a quick and strong undertow. When I feel somewhat stabilized and my pain is lessened, I decide to tell Astra in a few sentences about my current situation, believing that my own life experiences can enlarge her repertoire of possible narratives from which she can draw.

My own crisis lasts for about eight months and, at different points in our work together, I experience waves of sadness, disillusionment, and uncertainty about the future. The shards of my own life are now dumped on the shoreline at high tide along with Astra’s. So much for the "individual" lives of women.

Our work moves forward despite changes in the high tides and low tides of the therapist’s life. I seek help from a colleague regarding my own challenges.

***************

“I want to get back to your sister today. What did you do when your sister wasn’t around? Were you anxious?”

“Oh, yeah. She got married when I was fourteen; I was furious. I hated the man she was going to marry, not because there was anything wrong with him, but because he was taking her away from me. I felt a tremendous betrayal. Hah! And that’s when I stopped talking.” Her voice and chest are puffed out. The child is feeling her power again.

“There I was in this big house with just my parents. My brothers were already gone. I tried everything to let them know how upset I was. Nothing worked. So I decided to try the silent treatment. It worked! They took me to a psychiatrist when I was 13. For a while I gave him the silent treatment too, but then I started talking. I got the Rorschach test and something about draw a man. I thought it was a gas. Then he wanted to figure out why the men were all facing away from me! Like I would tell him anything about the men in my life.”

With a triumphant voice, she continues: “Somehow, after that, things were better. My father watched his language. You know, in second grade, I knew every four-letter word there was. They made an effort to be civil to one another. They kept the sarcasm to a dull roar. And that all felt very powerful to me.”

“I can see that.” I smile.

***************

How did this sensitive and bright young female child growing up in such a tumultuous household deal with frequent moves, relate to peers at school, experience her young, maturing body? What knowledge and wisdom has Astra learned about herself as a result of her seizure disorder? To her story I bring the piles of notes I have stored from my work with other children and adult women with seizure disorders.

“I had my first seizure in sixth grade at school,” Astra tells me.

“How did you deal with this?”

“Well, all of the children laughed at me. I thought, how would I go to school the next day? Then I realized that I could do three things—feel like shit, be embarrassed, or talk about it. Even though I was still embarrassed, I took the attitude that if you laugh at me, you’re the jerk, not me, and it worked! I remember vividly that night asking my mother about what was in this body of mine. I’d lift up my skin on my arm and, you know, pinch it and say, ‘Mommy, what is under this pink skin?’” She pulls up on the skin of her left forearm. “But no one wanted to talk about it. And my menstrual cycles, too. I got no information. Nothing.”

“So the bright sixth grader used her good mind to deal with what could have been a disastrous turning point. Instead, you fought back, took action. Is this accurate?” More empowerment.

“When I was 10 years old, my sexuality wasn’t up to my sensual body. I got the wrong attention from men for the wrong reasons. I felt very threatened. My father’s golfing partner and other friends.... Once one of them cornered me and my sister out on the porch. Another time, it was the parent of a child when I was babysitting.”

“You mean the father, don’t you? Not a parent, not the mother,” I clarify.

“Oh yes, of course, the father.” She is silent for a moment, pensive. “Of course, the father. I had some not-so-pleasant experiences. I despised my body. I realized that I had powers that I was not comfortable wielding. I would think, I want you to pay attention to me the person, not my body. I started feeling there was something very wrong with me. I felt I got weird and suspect attention. I would try to cover my body with these big T-shirts. One summer I was so miserable, I spent the whole time in the hammock just to get away from people.”

“So to protect your psyche and your body from men, you had to stay away from all people, everyone. Right? Did you tell your parents about these ‘friends’ of your father’s?”

“I did, but they laughed it off.”

“That’s a familiar story here, both the event and the response, and, of course, it saddens me greatly.”

“Did you say protecting? You were protecting the French tutor?” Her narrative isn’t clear to me, and my own anger is growing, ladened with my own childhood memories.

“You know, if my head had been where my body was, I might have welcomed their advances and thought it was exciting. As it was, I was scared to death. I remember having thoughts standing in front of the mirror, and I became aware of all this power I had—which is actually why I think I keep this extra weight now. Because I am tall, well proportioned, and when I’m not carrying this extra weight, I have a drop-dead figure. And when I was 15 or 16, this was causing me some awkward moments. The men would look at me and be thinking one thing, you know. It’s hard for me to conceive that so many of these men didn’t realize that a 16 year-old was a virgin. I mean, I wasn’t even making out in cars with boys my own age. I was really totally inexperienced.”

“I’m sitting here getting angry with what you’re describing,” I tell Astra. “What do you mean if my head had been where my body was? These experiences were not a reciprocal thing. It didn’t start out as two mature people enjoying each other. They took advantage of your age and inexperience. I don’t see the power coming from you. You were imposed upon—objectified.”

“I was a desirable object,” she tries to explain.

“By whose standards, yours?”

“Well, no.”

“I have to get back to this. You are fast to say that your own body is cursed in some way, being ahead of your head. Where is the curse here? Your body was growing at its own rate. It was the men who were out of sync, not you.”

“Well, I meant that I matured early.”

“It sounds like you blamed your maturing body and then that excused the men. That’s what I was hearing.”

“Oh, no. I was furious at the time,” she adds.

I refuse to let it drop. “Again I remind you, every child has the right to feel comfortable in her own body and to have the right to experience the pleasure of self-ma-.”

“I was going to say the pleasure of self-mastery, but I can’t accept the master part of that word, especially when referring to a female child.”

“Well, let’s see. Maybe I can help. How about self-mistressy?”

We both crack up with laughter.

“These word problems are not so easy to solve,” she says.

I nod. “That’s right. It takes some thinking, doesn’t it? Getting back to what I was saying: Every child has the right to feel comfortable in her body and also to have the experience of pleasure in gaining the skills to cope with her environment. In your case, experiencing your growing body as a pleasurable event was diminished by these men older than yourself and compounded by the feeling of being out of control already with your seizure disorder.

“Parental acknowledgment and support and input from the environment help a child to achieve a sense of entitlement to experiences that feel good—to gain the self-confidence and pleasure in getting these necessary skills. Your environment, both at home and in the community, was hardly supportive and stable. In fact, it was dangerous for you. You had to protect yourself.”

“You know, when I allow myself to examine all of this and to care so much again, I feel so much pain and outrage. It scares me to think about it—the significance of it all,” Astra says.

“I understand. I understand, and for me this is also painful because, in my practice, I have heard so much about predatory adult men in female children’s lives. It continues to overwhelm me with sadness. We should never be ‘therapized’ into forgetting our personal experiences. Never, because these experiences inform us greatly.” I decide not to tell her how well I know this.

Music and Seizures

Today, on my walk, the October lake mountains are full of reclining female forms, long and endless curving torsos, a firm breast here, a swollen belly there, buttocks against a knee, a full thigh, an extended leg. Patches of color lie above her silver blue lake. Swells of sunlight cross the mountains of her body, scooping out areas of darkness and mystery. Clouds touch the mountains and lie between the great forms. The mountains are washed with ribbons of sunlight. It is difficult for me to pull myself away from the lake today, but I bring back to the office the tones, forms, and colors of the lake.

At this point, I decide to share with her my own childhood experience that I call “cellobodyknowing,” hoping it will soothe her.

At this point, I decide to share with her my own childhood experience that I call “cellobodyknowing,” hoping it will soothe her.

“I have another personal story to share with you. Are you ready? Music school was my second home from the time I was 8 years old until well into high school. I was a scholarship student at the Greenwich House Music School in New York City. Each week I paid my fifty cents, and I got a little white slip of paper in return, which I put in my cello case. For fifty cents, I got a weekly private cello lesson, a class in music theory, and a string ensemble class that filled my Saturdays. It entitled me also to a free cello, without which I could not have lessons. I didn’t know, until many years later, that this school was a well-known music school for gifted children.

“One of my earliest memories was being taken into the locked instrument room by my cello teacher and being fitted with a new cello that met the needs of my growing body. We made this journey for a quarter size cello, and when I got older a half size cello, a three-quarter size cello, and finally, a full-size cello. I did not know that I was in need of a larger instrument, but my teacher did. I remember the warm body scent and touch of my teacher’s breasts against my left shoulder as she leaned over to measure my fingers on the fingerboard. She would then stand away from me for a moment and examine the relationship of the new larger instrument to my overall body. Were my hands comfortable? How did the cello feel to me? Yes, it would feel a little bit strange and large at first, but I would grow into it fairly soon. When my teacher was satisfied about which size instrument it would be, she would then involve me in the final decision making. If there were a few cellos in the correct size, I would have the chance to play the instruments and pick out the one that sounded the best to my ear, or more likely the one whose color, smell, and patina I was drawn to.

“For me, the musty scent of the old instrument room, the muffled sounds of stringed instruments coming from the practice room upstairs, and the warm body scent of my teacher were the events or sacred markers celebrating the changes and special needs of my growing body.

“You see, an ordinary secular event, being fitted for a larger cello by my beloved music teacher, became for me a sacred event of great meaning, and my ’cellobodyknowing’ was a core source of knowledge for me.

“Now I know for sure that I heard and felt music through my abdomen and groins long before I was taught that ears were the primary sense organs for hearing. My earliest and most private sensations and conversations were with my cello. No one ever told me that hearing in that way was not in the natural order of things. What I call my cellobodyknowing was one of my deepest understandings about what is true, beautiful, and good.”

It is only much later in our work that Astra tells me she loves this story because she understands that I value other ways of knowing, other than what we were taught. She knows that I appreciate that she has other ways of experiencing through her body.

“Good, that’s what I intended,” I say with a smile.

“Today, can we get back to your business? I feel I don’t know enough yet to be of any help to you. First, how did [material deleted to protect privacy], and what do you need now from me?”

“Okay, I’d like to start a little before that. I was exercising near the lake one day, and I had this idea that would help women. I never expected that ten years later it would be so successful that a conglomerate would want to purchase it. I was surprised about the success of it all because I never started out with the idea that I wanted to climb the corporate ladder or make a lot of money. My motivating drive was about doing something that would make women’s lives easier, stemming from a deeper place that is not all that clear to me yet.”

“So your success story of the American dream gave you the eventual economic security that many women hope for, but your idea was embedded in something larger?”

“Yes. To answer your question, when we first incorporated, after I invented this product for women, I had set things up so that … [material deleted to protect privacy] I had to get lawyers. It was awful. It took time and money, and then I had to buy the shares back, not at the original price, but at the current price. It was so unfair.”

“Beside being unfair, it was a terrible betrayal for you. A loss of something and someone you believed in and trusted.”

“So my questions are, should I leave the business now that it has been sold to the conglomerate? It’s not my philosophy to go this corporate route, where the sole interest is in profit. I have a contract for one year, and the company will soon want to renew it. I just don’t know what to do. What do I want? The ‘shoulds’ of it. What would be right for me? [material deleted to protect privacy]

One Orienting Map

This week, my office schedule has been very heavy, and we have a late session. It is the time of the winter solstice. The full moon is very bright and very high in the night sky. The pine tree outside our window places a moving and lacy pattern in front of the white lunar disc. I turn the lamp down so that we get less of the artificial jaundiced light of the Edison bulb and more of the blue white lunar light. We are now, in this moment, not the woman who comes for help and the woman who acts as guide, but two women bathed in the same ancient light.

In this light, I decide to introduce some new concepts: “Are you up to a mini-lecture? I want to say a little about the various components of therapy, at least the way that I practice here. I was looking over our work together, and I realize that I have forgotten to go over one of my maps with you.”

In this light, I decide to introduce some new concepts: “Are you up to a mini-lecture? I want to say a little about the various components of therapy, at least the way that I practice here. I was looking over our work together, and I realize that I have forgotten to go over one of my maps with you.”

“Sure. Go ahead.” She grabs her spiral notebook out of her purse.

“You don’t have to copy any of this because I’ll give you some cards I have made for you to take home that will have this information on them.” I pull over the large easel that I keep in the corner of our Inner Room.

“I call this my A, B, C, S, R diagram. The way I see it, therapy here occurs at a number of different levels. First, the affective level. This level has to do with your emotions and feelings, what you say about what you are feeling, which feelings and emotions are evoked by which people, events, or memories, and why. The second is the behavioral level. This is about what you do about something, or how you act toward people or events, or what you do after you have new knowledge, or what behaviors you might choose in the future. Then the next is the cognitive level. This has to do with new information, new data, and new ideas that we bring to our work together. It might be something you read, or learn yourself, some new knowledge, or it might be something that I learn from you. It might be some reading I suggest to you. Broadly speaking, cognition pertains to our mental processes of perception, memory, judgment, and reasoning.

“Now we get to S. This is the spiritual and philosophical level. This is about our philosophical world view, our religion, our spiritual way of being in the world. Are you with me?” She takes a few moments to formulate her thoughts.

“Yes. This is interesting. I think that I covered some of these ideas in a graduate course I took with your colleague Betty. The course was about the creative process. Somehow in the course we got into the question of how do we know?”

“Good. Maybe Betty can join us at some point in our work together. Then we get to the R, the relationship of therapy itself, the experiencing of each other in this process together. The shape and direction our work takes will depend on what the two of us create together here, what you elicit and draw from me about my own thoughts, beliefs, expectations, meanings, life experiences, and what I draw from you in our dialogues together. The emotional component is important at this level as well as the faith we both have in the process.

“All of these levels of work are cradled or held within a female body, which, of course, houses your mind and all of your personal experiences. All of the work we do here takes place in a particular period of history and in a certain culture. I’m not saying this is a complete diagram at all, but I have found it useful in thinking broadly about our work here together. It also creates a more egalitarian way of working because now you have a better sense of my own map, I hope.”

Her mind is quick. “Are you saying that this diagram wouldn’t apply to men? Oh, but I can see right off that ‘he’ wouldn’t be housed in a ‘she’ body.”

“Sometimes, but not ordinarily!” I grin. “Let’s hold that question for now and see what your answer would be as our work together continues, if this is okay with you. I think that your own answer to that question is more important than mine.”

“Okay. I need to think about all of this.”

“Good. You may have some additional ideas of your own as we go on.” With this new joint negotiation, we move forward.

**************

Over the next few months, I continue to learn from Astra what it takes to make a small creative idea grow into a large business. The strategies, the wisdom and planning required, the amount of energy and work and travel and late nights and speeches. I learn about the new corporate conglomerate that she sold her business to. But I also hear her hurt, betrayal, fatigue, felt invisibility, and abuse and see how much they are templates of her earlier life. I see how she has gone from a divorce into a changing business in which some people are equally abusive.

Astra is considering the economic ramifications of not renewing her one-year contract. I wonder whether I have the knowledge, wisdom, savvy, to be practical about her future financial needs and security over her lifetime. I have to be honest with Astra about my own ignorance, ask the questions I need to ask, and be educated by her so that I can be of help in supporting her in her own decision-making process. We discuss which big-time lawyers to use, how to keep her rights to founder status in the company.

I am a product of a marriage of the early fifties. Although I managed my own money before we were married, I experienced a hiatus of many years while raising our children, in which family funds were managed through my husband’s office and checkbook. Even when I returned to graduate school and full-time work, our finances were pooled, and the money I earned was deposited by my husband into our checking account. It was only after my own doctoral studies and the eventual opening of my practice that I began to understand the economics of women’s lives. I then seized back the right to manage my own money as I had before my husband and I were married. I have no idea what a woman living alone would need to support herself and provide for herself.

As our therapy continues, it becomes clear to Astra and me that she should not stay on with the new conglomerate that has purchased her business, whose main motive is now profit. Nor should she stay in an environment that is so toxic to her health. We stay in a holding pattern. We are reluctant for her to leave her work until she has examined in what ways she allows other’s behavior and presence to ensnare her in the old pain.

However, the day finally does come when she is ready, happy, and eager to leave her business.  I suggest that we visit her old office and have a celebration event. She is clearly delighted. She picks me up at my office, and we drive there together. This is the beginning of a number of activities that we engage in together outside my office because it is a ritual of importance, a special day in her life.

I suggest that we visit her old office and have a celebration event. She is clearly delighted. She picks me up at my office, and we drive there together. This is the beginning of a number of activities that we engage in together outside my office because it is a ritual of importance, a special day in her life.

Her office building sits in a pastoral setting. It is more like a series of cottages than the large industry that it is. The buildings are done in this way to reflect a humanistic philosophy. As she takes me through the large warehouse and work areas, it is evident that her staff truly cares about her and that they relate to each other in an open and generous way.This field trip reinforces my belief about the idea of pushing the geography of therapy out into the community. Thus, therapy moves from the personal to the communal experience.

******************

I continue to mentally sketch Astra’s life’s journey with an ever-expanding map. On a good day, if I am as finely tuned as I would like to be, I discern the various chronological voices seeking expression. These voices have different capacities and special learnings. The voices are sometimes in harmony, sometimes discordant.

Astra continues her ‘business’ narrative. “As I reflect back on things, I realize I felt trapped for years in the business. My life has been hampered by the business. I realize I have to throw away the baby with the water. I knew that if I didn’t sell the business, I would never have a life beyond it, but now here I was in this mess.”

“So, you were in a mess because of certain things you have set in motion for yourself to have a life for yourself. This mess is of some benefit to you then.” Again empowerment.

“I hadn’t thought of it that way.” She pauses, then begins again with the words of the recurrent theme of her early sessions with me. “I don’t have a husband, children, lots of friends, a good life. I’m a failure in my own eyes. Yesterday my robe caught fire when I was making a fire in the fireplace….”

“My God. What happened?”

“It was fluky, and it was funny from a distance. But again, see, there was no one there. This power of the witness....” Her voice trails off. “Then I said to myself, ‘Astra, this is typical of how you have conducted your life. There’s nobody here when you need them.’ I feel like a child who can’t make choices about conducting her life. As a child, I remember being really scared watching TV when someone was accused of being guilty when they weren’t. That’s how I felt, unfairly blamed.”

“Yes, but the young child didn’t have the words, knowledge, or insight to say this. It is only now that you can reflect back on this and try to make some meaning of it all. Then it was just terrifying to you.”

![]() The fearful life of the young child during these years is expressed now in a poem she has recently written. She unfolds it slowly, cautiously, lovingly, and hands it to me.

The fearful life of the young child during these years is expressed now in a poem she has recently written. She unfolds it slowly, cautiously, lovingly, and hands it to me.

Dark violent nights,

I love you dear

Screaming fights,

You have nothing to fear

Fisted caresses,

You’re lovely in white

Bloodied dresses,

Such a pretty sight!

Hit again, again–

It’s alright,

I hate men.

Daddy loves you.

“You see, this was my experience. Do you understand it?” she asks me.

“The beauty of a poem or a work of art is that it speaks to us so directly. It speaks for itself. I think to summarize your poem takes away from what it is in the first place. It speaks from your heart to mine. Having said that, I’ll try.

“The left column looks like your direct experience of your mother’s abuse by your father, and the right side looks like the public persona, the lie they showed to others.”

“Yes. But do you see the next to last line? That’s me in the middle, between the private experiences and public voices. My voice. Do you see?”

“Yes, now I see it.” We sit now in the silence of childhood fears remembered.

*********

“I want to get back to something we’ve talked about before," I say to Astra one day, "and that is your occasional glib, sarcastic voice. You use it right after you say something tender or serious. Why aren’t you taking your statements seriously enough? As soon as you say something tender or serious or profound or insightful, you negate it with this other voice. What is it you are doing? Can you tell me?”

“It’s the glibness that comes out of my anger and pain, I think. I’m sorry.” She begins sobbing.

“It’s nothing to be sorry about—just be kinder to yourself. You deserve it. I understand what you are saying here. The glibness covers the powerful feeling.”

“Did you know that my mother valued girls? She didn’t want sons. My father did nothing to help his sons. They were on their own,” she says when she stops sobbing.

I hypothesize, “You know, this is a perfect example of typical gender roles - that is, the girls being devalued and the boys valued - being confounded by family idiosyncrasies. In your family, the boys are put down and female children are valued by their mother, but all of the children in your family, and your mother, are locked in a submissive relationship with an abusive man.”

We sit again in another painful silence.

********************

It is a warm spring day today. The rain on the south window of the Inner Room obliterates all boundaries. The sky dissolves into trees, trees into grass, grass into earth. I have a great love for this woman sitting before me. My ability to demonstrate my capacity to understand her helps Astra to move forward with her narrative. She has allowed me to hear her truth as she knows it. She is less imprisoned now in her memories of compromise and conformity for the sake of acceptance and love. Her gifts of mind, her courageous attempts to fight back for what she needed, are in the light of day now, and there is a witness to these retold events. This is what happens when a woman freely chooses to liberate herself in the presence of another woman committed to the same goal.

Conversation in therapy is different from ordinary conversation. Our life stories are told to different people for different purposes. As a therapist, I have a privileged position in hearing another woman’s life story. In the way in which I work, I have chosen to allow some of my own truths to be known to her in areas that seem to match her needs, because I believe that this is one of the significant ways that healing takes place for women. Familiarity with and knowledge about my own map journey add authenticity and validity to Astra’s life experiences.

As her therapist, I have been given a cultural authority over the decision about what events in her life are worth attending to and what alternative meanings she might possibly place on these events. Women’s therapists are, after all, culturally sanctioned interpreters of women’s life experiences and remembered stories. Therefore, I must be sure through whose eyes and for what purpose I spot a “good story” and for what reason I want to know more.

********

I have always been impressed with how women are able to navigate through different situations that can come up in our work as a result of living in a small and intimate community, and how well we two do this. We must have the ability to be aware of the rules and roles and patterns of behavior, which change, as relationships move from the professional domain to the personal domain, or the reverse.

Today, Astra wrestles with a dilemma as a result of her friendship with my daughter who lives in our community. We do not have the safe boundaries that women have in large cities, where a therapist may have a personal life in a suburb and a professional life in an office in Manhattan. This difference adds a rich dimension to our work and leads to deeper, more self-disclosing narratives.

“You and your daughter are the most important people in my life right now. I feel so loved and acknowledged by you both.” Crying, Astra muses, “It’s funny, I’ve been thinking how the same person can be one person’s therapist and another’s mother. That’s very interesting to me.”

“I know what you mean. I’m still the same human being in each situation, you know, the same human spirit.”

“I know.”

“But there’s at least one difference. You got to pick me!”

“And we have no personal history,” she postulates.

“Right. But we are creating a history now. I remember writing in my journal one day shortly after I started my practice twenty-five years ago, that being a mother and being a therapist are similar. I wondered why I got paid for what I do now as a therapist and why I didn’t get paid for it then as a mother! I realized that a therapist’s skills are valued by the culture at large and a mother’s skills are not. As I began to think about this, I realized that in either case the core ingredients were love, hard work, and an awful lot of faith, ancient wisdom, and creativity.”

“Right. But we are creating a history now. I remember writing in my journal one day shortly after I started my practice twenty-five years ago, that being a mother and being a therapist are similar. I wondered why I got paid for what I do now as a therapist and why I didn’t get paid for it then as a mother! I realized that a therapist’s skills are valued by the culture at large and a mother’s skills are not. As I began to think about this, I realized that in either case the core ingredients were love, hard work, and an awful lot of faith, ancient wisdom, and creativity.”

More experiences of her seizure disorder emerge. Yesterday afternoon she saw flashing geometric images in patterns of black and white and visited a place she couldn’t name. When she returned, she found a large floor plant overturned. That’s one of the ways she knows that she has had a grand mal seizure when she is alone.

“You know, I was snorkeling with a friend a few years ago, and I had a seizure in the water. If my friend hadn’t been there, I would have been a goner. You know, I worry about flying and getting a seizure.”

Astra could be one of my daughters now. She is in my thoughts when she drives or takes a plane or when she is tired. I feel her loneliness even when she is not here in the office. I want to soothe her suffering, and I am very concerned about the lack of good medical care for her seizures, but she is not ready to meet with a neurologist.

“I know that you are afraid to lose your driver’s license, that if you tell the truth about your seizures, it will be taken away from you. What about going out of state? You’ll be freer to say what’s really going on, and you are not the first woman sitting in that chair to be concerned about this. Plenty of other women have the same fear that you have.”

Last week she had a petit mal seizure while talking to a large business group at a meeting in Georgia. She checked with one or two friends, who said they didn’t notice it. Years of “Googly eyes’” practice in controlling her eyes has paid off again.

“You know I wish I could find out more about the research about—I wish I could have an intelligent conversation with somebody about the research on seizures and hormones,” Astra tells me. “My past experiences have not been good. I was often overmedicated.”

“Well, I don’t really know who’s out there for you to see. I need to think about this. What I can say is this: I don’t know if you realize how little research has been done on women’s lives in all areas of research—sociology, psychology, anthropology, history, education, archaeology, the arts.

“In the late sixties and early seventies some women who had been active during the Civil Rights movement came home and, with other women, started to do an analysis of oppression in their lives in consciousness-raising groups. They and other women started to question the places they studied or worked in: Where are the women in my field of study? Where are the works of their minds, the artifacts of their lives, their role in history, their works of art and music? These women and others out in the community started their own areas of research and study to address these absences and silences. Considerable new research is out there, but I am not sure about the research on seizure disorders and hormones.

“I was recently astounded to learn that the data for the Stressful Life Events scale—you know, the one that lists categories of stressors such as losing a job, buying a house, getting a divorce—that so many of us had been using for years in our work, was done on twenty-one-year-old white males in the navy! And more recently, I learned that most of the research done on post-traumatic stress disorder was done on male veterans. My profession has used these studies unilaterally for decades.”

“It would be interesting to see a woman’s list. I could sure make up one,” she smiles.

“I’m sure you could.”

“Why were we left out?”

“Well, I can give you a few of the reasons. First, it was generally men doing the research, and women’s lives were not seen as worthy of study. Secondly, we complicated their research projects by the wonderful changes occurring in our bodies each month and by our pregnancies. Male researchers would have to factor in more components to their projects because of the richness of our biology and physiology. It was simpler to use men.”

“That’s mind-boggling. I can’t believe this.”

“Well, look for yourself. I have some materials out in our women’s studies library I can give you to read.”

Astra spends the next few weeks doing what I call a form of implosion therapy. Reading everything I have on the subject to blot out the old bits and fragments and strings of knowledge in her body and fill it with new knowledge.

She comes in a few weeks later, saying, “Well, maybe that’s why I can’t find any intelligent people to converse with.”

“Well, you may just have to push for the dialogue somewhere. You may have to start it yourself often. That’s what most of us have to do, you know.”

*****************

Today Astra is anxious to get back to one of our sessions in which I had introduced the concept of the inauthentic self. [A term that dates this period of therapy; a term I would not use today.]

“So, not to make waves and to be accepted,” she reflects, “that’s what I did. Cloaking my true feelings and putting on different personas. I see that it started way back. In my family, trying to figure out how I was going to fit into these different social groups when everyone was bigger, more powerful, and got their own way. I was like the doll in lots of people’s eyes. I see now that the outer protection really does serve a purpose. I had forgotten that there were personas. I need to be more conscious of what I’m doing.”

“Yes, it’s hard to know your true essence when so many times your response came out of pain or as a protection.”

“I learned to let go of my feelings because that’s how I got hurt. I learned to separate instead of being all there. I became discriminating.”

I expand the narrative by examining her choice of words: “What do you mean by discriminating? Can you be more concrete?”

“I chose what I would put out and what I wouldn’t. I learned that I could cloak my behaviors. I can choose what other people see of me and not be there. I did that all the time. As I re-examine it, I see what I did.

“When I look over my childhood dreams, I realize now that there was a lot of dread. I dream houses all the time. Houses are personal markers for me. And another thing: I think it would be interesting to probe my relationships with women. I always thought that womanhood was a special club, you know—me, my sister, and my mother—and that men were the outsiders. I thought about what you said last time. What is this power that my business partner has over me? I see now that I am always scanning my business partner, but I don’t know why.”

“When I look over my childhood dreams, I realize now that there was a lot of dread. I dream houses all the time. Houses are personal markers for me. And another thing: I think it would be interesting to probe my relationships with women. I always thought that womanhood was a special club, you know—me, my sister, and my mother—and that men were the outsiders. I thought about what you said last time. What is this power that my business partner has over me? I see now that I am always scanning my business partner, but I don’t know why.”

“Scanning. That’s a good choice of words because it’s what frightened children do.” I add, “Adult women often need to do this too—but let’s stay with the child. Children who don’t feel much protection from their parents keep checking things out, scanning for signs. Is it safe? If it’s not, where do I go? How do I make it safe? Is there anyone here to help? That’s what young children do in a household like the one you grew up in. It’s of interest to me that as an adult you did that with your business partner, this same scanning. What has she set off in you that feels so violent, and what is it you want from her?”

“I don’t know. I need to think about this. I was at a meeting the other night, and I thought, when my life is over, who is going to know the person I am today? Maybe they will only see the drudgery, the achievement, and the glitz. What will people say of me when I am gone?”

“How about you enjoying your stay on this earth now? I like the saying that God is present whether welcomed in or not.”