Alison’s been shot

At 7:45 that evening, while sipping a cup of chamomile tea during a break from my writing, I receive a call from Alison’s husband, Harry.

“Judith, Alison asked me to call you…Alison’s been shot.”

I almost go on with the conversation, expecting that we will start talking about the weather, or the beautiful viol de gamba bows that Harry makes. Then my brain registers the words. I ask Harry to please repeat what he has just said to me.

“Alison’s been shot. She’s on her way to the operating room. She was shot at work today. She wanted you to know."

“How is she? How serious is it?”

“I don’t know yet. She’s in the operating room now.”

“I can get some information. I’ll call you right back,” I tell him.

I am already dialing the operating room before I even know what I will say. I have access to the operating room because I know many of the nurses and physicians there. My Nurseself takes over.

“This is Judith Koplewitz. I am a friend of Alison’s. What is her status? How is she? How life-threatening is it? I have the family’s permission to ask.”

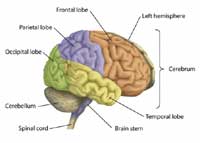

The nurse answers, “Just a minute. Her surgeon is right here scrubbing.” My message gets repeated to the surgeon as I listen. Then the nurse comes back on. “Well, she’s okay neurologically, but she has some fragments in her brain. She must be surgically explored and the fragments removed.”

I call Harry back. He has Alison’s parents, who live in Connecticut, on another phone line. They are driving up and are greatly relieved to hear that she is okay neurologically.

I am able to get a few more facts from Harry. After giving me a massage in the morning, Alison had gone to her office later in the day to give her close friend and former dance teacher, Nancy, a massage—an overdue Christmas present. A man had gained entry to the outer office and, after taking some money from both women, ordered them to lie on the floor face down and then shot them at close range.

I am somewhat relieved by the information I received from the operating room, but I am still in a state of shock. I decide not to go to the hospital that evening, knowing that Alison will first go to the Intensive Care Unit and will probably be sleeping. I spend most of the night pacing the floors and finding excuses to go up and down the stairs of my home. I sit at my computer and use my fingertips to weep. The organization of sentences, the concrete structure of the words on the screen offer a kind of ordered, visual sanity in a now chaotic world.

**********

Still full of anxiety and disbelief, my daughter and I drive to the hospital. The area outside the Intensive Care Unit is filled with worried and tearful faces. People are standing, squatting, sitting, and holding each other, greeting each other with loving hugs. As I scan the group, and as people introduce themselves, I notice that many of the women and men there are artists and healers in our small community. As my daughter speaks with people, I realize that many of them are also her peers and friends.

I give Nancy a call and explain the problem.

“Well, I asked for you, and that’s what I want. Why should I see someone I don’t want and don’t know?” she says assertively.

“Well, that depends on whether you are feeling in crisis. If you are, then perhaps you should speak with someone at the hospital.”

“That’s settled! Good. There are no house rules when I’m out of here!”

“Will you be able to call me? I’m not clear yet on the extent of your injuries.”

“Neither am I, but don’t worry, I’ll get there.”

The Power of Friendship

From Nancy’s records I get a sense of the urgency in the Emergency Room that day:

“Acutely agitated female says she can’t breathe...occipital entry and exit wounds discovered...moderate bleeding ...markedly decreased breath sounds in left chest...gun shot entry eighth rib...intravenous started...left internal jugular line placed...left side chest tube inserted...urinary catheter placed...chest x-ray...skull x-rays show metallic debris in the posterior aspect of the skull...large bony fragments were driven into the left transverse sinus...another bullet fragment lacerated her...Fracture of the left occipital bone...”

“Placed on operating table...head shaved, two defects in the scalp noted...entrance and exit wounds found...horseshoe incision made with a scalpel...incision made to the bone...flap retracted with fish hooks...defect size of a quarter where the bone was pressed in...clot and necrotic tissue and some brain herniation ...fragments were removed...bleeding...gelfoam used...small sutures to repair...some leaking through the sinus...bandaged.”

Alison’s report is remarkably similar to her friend’s, but the bullet entered her head in a different location, and she has no chest wound.

I have many questions in my head today, somewhat sequenced and ordered. They will be answered if they meet both women’s needs, not mine, and in the time and tempo that contributes to their healing.

As a therapist, I need to get into the scene of that afternoon as they saw it, heard it, felt it in their bodies. There is no textbook separation here between what is body and what is mind. There is no Cartesian controversy or theorizing here, no split between what part of this woman belongs to surgeon and what part of her belongs to therapist. I must find my way to where the bone and spiritual fractures meet in a woman’s body. I need to know what has happened to these women. How will they deal with the experience of another human being intentionally harming them? What pain is visiting them today? Has either woman experienced any other forms of violence before this shooting? If so, what thoughts or memories does this event trigger—did I just say trigger? I can’t believe it—and I want to know what have been the consequences of the shooting in terms of their friendship. Then, too, who is their support system, and how is it working? My notebook is ready.

A mutual friend drives them to my office. Alison is tiny, small-boned, birdlike, with brown hair and eyes. She wears something that looks like a dark green and purple gauze hat draped over the left, shaved side of her head. (It is surgical tubing, she later tells me, that a friend dyed in different colors for her.) It is to protect the hole in her cranium left by the bullet entry. She is dressed in a loose cotton blouse and ankle-length skirt, both black and dark purple, and wears dangling silver-and-amethyst earrings. She appears so fragile that a breeze would make her bend like a young, slender bamboo reed, but that appearance belies her considerable strength.

When the women head down the narrow hallway to my Inner Room, Nancy walks tentatively, holding both arms out and using the walls to guide her movement. Alison walks closely behind, watching her friend.

Alison takes the lead voice and gets to work immediately. She begins with her intuition, her sense that something was wrong that day in her office at the Massage Center.

Turning to Nancy at her right, she says, “It began for me while I was still working on you, because I heard somebody out in the stairwell. I knew the door was locked, and I heard the stairs creaking, and it was so weird, because there was something about the way the stair creaked that I got really scared. But I’d just seen this suspense movie called The House of Games the night before, and…” She leaves her unfinished thought suspended on the creaky stairs. “I was aware that somebody was out there for about fifteen minutes, waiting, and I was just saying to myself, ‘Alison, don’t worry.’”

“Yes, and I was aware of not wanting to worry her,” she answers, turning again to Nancy. “I was probably really done with the massage at about ten after the hour, but I kept working for another five minutes, hoping that this person would go away.” Her voice is softer now. “I went into the closet to look out. There is a little window there, and I peeked out of the curtain. I looked at him, and he looked, you know, well, harmless enough. I said that to myself. Then I went back out, and as I was opening the door to go out into the lobby, I remember I took this deep breath and said to myself, ’Alison, be brave.’”

Trying to get the mood of the scene, I ask, “So, again, you sensed a potential problem?”

“Yes. I don’t remember in all the years doing massage ever being afraid to go out, even when we have had weird people out there sometimes. It’s like there was something that made me really afraid to go out there.”

“Yes, and that’s one of the questions for myself: Why didn’t I listen to that? Part of me wanted to come back and say, ’Nancy, there’s somebody out there, do you mind? He’s making me scared. Do you mind just waiting for half an hour and maybe he will go away?’ But I didn’t want to get you scared.” Her eyes dart left and right, up and down as if she is watching the scene she is in on a large movie screen in front of her.

“You wanted to protect your friend and client?”

Trying to see the scene clearly and knowing that Nancy is trying to recreate the scene as well, I ask, “Where was the gun exactly?”

“It was at his waist level pointed at me, and I just got hot. My whole body went hot and numb, and then I immediately went into a dream reality. I didn’t connect that it was a gun, either. It looked really small. I thought, That can’t be a gun. He waved me back with the gun and said, ‘Get back!’ and I said, ‘No, you get out of here!’ I was screaming at him.” Then again turning to Nancy, she adds, “I’m surprised you didn’t hear more because I was really yelling at him. He was still on the other side of the doorway, but the door was behind him. I pushed my whole body into him trying to get him out so I could shut the door again.”

What I am actually able to observe is that her pupils have dilated, her breathing is shallow and rapid. And from my experience as a nurse on a psychiatric ward, I can smell and see her fear. It sits in the air now as a cold, damp wind sweeps across her body.

At the same time that I enter the scene with them, I stay outside the scene sufficiently so that I am able to monitor both women carefully. Alison looks frightened and pale, and she is shivering.

“Are you cold?” I ask quietly.

“Yes.”

“You are also breathing rapidly. Try to take a few deep breaths.” She does this, and I tell her, “Guess what? I just happen to have a heating pad handy.” I plug in the heating pad and place it on Alison’s lap.

We are able to laugh briefly and break the relived terror.

“Can you describe his voice? High-pitched? Low?” I am trying to hear the scene.

“Did you sense he was scared?” I ask.

“Yes.”

“What I’m trying to do is have you get in touch with as many of your senses as you can about the experience. Try to give me as much sensory information as you can remember.”

Alison continues, “This next sentence is probably the only one where I really remember his voice. He said, ‘Now, I have to figure out how to get out of this town,’ and he sounded really scared. He asked about the cars. I told him where my car was, and I guess he must have walked over to the window. That must have been when he asked about the tape and stuff, which in retrospect I figure maybe he thought he would just tie us up and steal my car and go, but since we didn’t have any tape—I remember just like a long pause and then the gunshot. He probably figured the only way he would get out of town was to shoot us.”

I bring myself quickly back to the current scene. “Well, you don’t know if that’s so. Obviously, it had to be more than thirty seconds. I’ve been in a—um—not a shooting accident, but an automobile accident, and I’ve worked with other women who have been involved in a trauma, and these time sequences are very confusing.”

“Yeah, it was amazing. When the ambulance and rescue people came up, the police were asking me questions the whole time, and I was just watching you, Nancy,” Alison says, turning to her friend.

“What do you mean?” I ask.

Nancy in her wisdom attempts to soothe her friend. “Yes. You know what’s interesting, though, and I think you need to know this: Whenever I play it over in my mind with a different scenario, it always ends up being worse than what actually happened. One of the things that I personally don’t want to do is suddenly become a fearful person. I want to still maintain a trusting attitude toward life.”

I add, “And yet you must find some place for this violent experience within the context of your world view. The way you previously thought about your place in the world. Is that it?”

“Right,” she nods.

“Do you have anything you want to add to what Alison has been saying?”

“Pretty much every time I close my eyes and nap. It’s a little less intense now than it was, but whenever I am quietly by myself and close my eyes is when it starts.”

“Nancy, why did you ask Alison that question?”

“I don’t know. To compare, I think. I feel like I run it all the time, and it doesn’t seem to be just when I close my eyes.”

Nancy relates some of the situations in which she has become frightened. “I find that I am reacting to scuffling noises and sounds outside a closed door, which is what I think I heard before he entered the room. I can’t handle having a bathroom door shut, or pushing open a door and meeting some resistance.” (Months later I learn that there is more to this bathroom door story for Nancy.) “I feel that these negative images have been imposed on me, and in the context of my life it all feels very foreign.”

Alison turns to her friend again. “Sometimes, like today, I just woke up blah, I just didn’t feel particularly interested in anything. Or some days I wake up, and I feel sad. I know I have a good reason to, but I haven’t done any thinking about it.”

“Look, it is my belief that the right knowledge empowers us as women,” I interject. “I want to give you both a context within which you can consider the wide range of symptoms you’re both experiencing and also some idea about what you may experience in the near future. Some therapists think it’s best not to tell people in advance of their symptoms, but I am the kind of person who likes as much information as I can get when I need it. I find I do better with more, not less, information. So that’s the place I am coming from. What do you both think about this?”

Alison nods.

Nancy jumps in. “Well, it’s clear we already have many of the symptoms.”

Alison, in a faltering voice, says, “One question that I have for Nancy, and I think I might have asked you this in the hospital once, too, but I just need to make sure you are not mad at me. You know, for opening the door, or anything…. It stays with me all the time. This thought that I didn’t protect you.”

“Oh, God, no.” Nancy reaches a hand out to her friend. “It’s the last thing I would ever think about! If anything, I feel like you saved my life. What you did, the fact that you were able to go downstairs and everything. I have total trust and faith in everything that you did, and never, never would get angry with you.”

Alison is now in tears. “Basically, I guess I know that, but every now and then I need to hear it again.”

This embrace of friendship is a symbol of our healing process together, of women’s capacity to support each other with love during difficult times. The deep friendship, trust, and caring among us is a critical component in this process. I say “our healing process” because I respond as a woman as well as a guide, and the moral pain is always there.

The friendship I am seeing between Nancy and Alison is far from dismembered; it is compassionate and important to them both, and undeniably overrides the customary female conditioning to exist primarily for men. Janice Raymond has written that male biographers have been surprised at the intensity of friendship between, for example, Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict, Eleanor Roosevelt and Lorena Hickok, or Helen Keller and Annie Sullivan.

Nancy and Alison will go through their healing as individuals, of course, but they will also, clearly, heal together.

Transcending Violence

As their therapy continues in the months ahead, I have placed some side notes in my notebook. First, Alison didn’t expect this man to use the gun he displayed. Why not? Second, Alison didn’t trust her own intuition that they were in danger because she had watched a suspense movie the night before. How did watching this film stop her from trusting herself when she felt some danger on the stairs? Did this film condition her in some way? Did it override her wisdom? I am left with many more questions.

I discover that if I want to learn to shoot properly, there are men who will teach me. The teachers recommended to me happen to be guards in the local correctional facility. I am told about a gun club and practice range a few miles away where I can go and practice. I learn about different kinds and sizes of bullets, and which ones explode more and do the most harm. I learn about gun holsters you can hide on your person and magnetic ones you can hide above a door for quick use in your home. I am given pamphlets that state that an increasing number of women own small firearms.

If I name my activities counter transference, it stays private, personal, my reaction to a public event. If I call it rage and acknowledge the overwhelming official statistics regarding violence done to women, I have a right to stay angry. I have a right to label it this on my own personal map.

In the spring, when many of us are thinking about new growth and life, seeds and small plants, a 34-year-old music teacher is beaten and stabbed in her home by a prison escapee. Later in the year in a nearby community, a 93-year-old woman is beaten and strangled in her own home by a 22-year-old male stranger. At or around the same time, a 16-year-old female high school student is killed at a boyfriend’s apartment in a drug-related shooting. The following autumn, a 21-year-old mother with a 7-year-old child is abducted from her workplace by her estranged husband, who fatally shoots her and then himself. The reality of my own record keeping of community violence brings me considerable pain. It would be less painful, perhaps, to tuck this data away mentally, or place it in a separate file outside my therapy notes. It would be more “clinical” to fold away and separate my “community notes,” what has happened outside of therapy, from what has happened inside of therapy. To maintain my own sanity, I decide to have the community experience sit side by side with the personal experience of violence. Together they create the true picture. In this way I am able to bring together an ethics of justice and caring into my professional folder.

Women are not safe anywhere, not in our own homes or our rented apartments, not when we are at work, not on our streets, not in our cars, not as we hike or bike across our beautiful natural landscape.

Architect Leslie Kanes Weisman addresses questions of space and boundaries in her book Discrimination by Design: A Feminist Critique of the Man-Made Environment. In her analysis of the spatial dimensions of gender, race, and class, she writes about the social processes and power struggles involved in building and controlling space. She notes that there are double standards with regard to what constitutes public or private space. In public, women must constantly contend with invasive male behaviors such as whistling, clucking, sexual assessments or propositions, and obscene gestures, and must be on guard against more dangerous threats. “Women, thus unable to regulate their interactions with male strangers in public places, are robbed of an important privilege of urban life: their anonymity,” writes Weisman. “Women learn to be constantly on the alert, both consciously and unconsciously, in order to protect vulnerable boundaries from male trespasses.”

**********

They decide to sit together, support each other, and let each other know what’s happening for one another. Still, they are anxious. The everyday world that was previously taken for granted, so comfortable and sure, so safe and sane, so full of loving people, now feels overwhelming to both of them.

Alison says, “I am not sure that I can handle going into the lobby at intermission—so many people, so many questions.”

Nancy says, “You know, I was thinking—most women who have survived a crime don’t have this kind of community outpouring, this financial help. I wonder what they do.” Then Nancy turns to Alison. “I want to ask you a few things. How is your hand?”

The woman whose livelihood has so much to do with healing through human touch and discerning another person’s energy fields answers, “My hand feels like gauze. I can’t really feel everything when I touch people. The numbness blocks the feel of the energy.”

“Are you still having nightmares?” Nancy asks.

I add my voice. “I understand what you are saying about your healing process, but your mind-body was in survival mode.”

“Actually, I appreciate the nightmares. I think they are part of the healing, even though they are very frightening.”

Our caring community of people often lump the two women together in the same conversation. They are asked not only about themselves but about the other in the other’s absence. They both report that they have to work very hard now at keeping their lives separate.

“I’m very impressed at how you have both gone about your healing, collectively and individually. I have a concern, however, that you may measure your own healing through the other person’s progress.”

“Yes. I think we both feel this pressure now,” says Nancy.

Alison is feeling this more because her injuries are less extensive than Nancy’s. She still feels the responsibility because the shooting occurred in her working space. She feels the guilt of a person who has been a witness to another person’s suffering and feels a severe “burden of conscience,” as Judith Herman, a psychiatrist, has written in her book Trauma and Recovery.

But Alison has some questions of her own, and we shift away from Ed. “Where are you physically now?” Alison asks Nancy.

“I’d like to know what is your internal imagery about what is actually going on in your body in terms of your healing,” I ask Nancy.

“I’m not a doctor, but—”

“Excuse me for interrupting. The reason I ask is because there is a difference between the images and metaphors that come out of a medical diagnosis and those that come out of your personal experience of the shooting.”

“Yes, I feel now I am ready to do some work on you,” Alison tells her.

Nancy’s voice softens. “I know that you are the person I want to heal me.”

“Great!” the massage therapist answers, her guilt soothed.

As Nancy continues to try to search for meaning in the shooting, she explains, “One of my friends thinks that this incident was a means of selection. The reason we were chosen was because we are open to another form of cosmology. We are going to be passing this information on by teaching about this experience to others.”

I find it momentarily difficult to let Nancy’s statement stand. I have an immediate reaction to the phrase “means of selection.” I have a flashback of myself as a pre-teen watching newsreels, seeing piles of naked corpses of Jewish children and adults—the result of another “means of selection.” I let go of this intrusive image, knowing that it is mine and not Nancy’s, and bring myself back to the moment.

“Before we stop today, it helps me to get feedback from the women I work with about what has helped them. What has this time together provided for you both?”

Alison starts reflectively. “For me, it’s been a place to talk more deeply, beyond checking in with each other on the phone. Here we go beyond conversation. And there is time and space to feel and to process.”

“It was a place for me to tell Alison that she saved my life. I also got new information, things I didn’t remember,” Nancy says.

Turning to Alison, I tease, “Do you get that now? Has your guilt been somewhat assuaged?”

“I think so,” says Alison, more sure than in our first session a few months earlier.

At this point, both women agree that they have accomplished what it was they wanted to do together. They have reached a place of some reprieve, a nurturing space for the spirit. Both women have already made remarkable progress since the shooting. Although many challenges remain for both of them, they are working on their healing and have considerable support from families and friends.

The regulation of intimacy, the vacillation between self-isolation and anxious connections with people, the recurrent fragmented dreams and nightmares, the intermittent fatigue, and the scanning of and hypersensitivity to everything in their environment continue for months and on into years.

Nancy Alone

In Looking On: Images of Femininity in the Visual Arts and Media, Rosemary Betterton notes:

“Femininity, as defined in western culture, is bound up very closely with the way in which the female body is perceived and represented.”

How do I “see” this wonderful woman sitting before me? How shall I further describe her to you? Will I describe skin surface? Body contour? Clothes draped and fitted? The bullet holes and suture threads, invisible, but known to us? In this layering of a woman’s story, where shall I place her body and what shall I describe of it? What does it mean to look at a woman from a feminist point of view? How do I not carry, not be a vector for practices that might work against our own visceral freedom?

In writing about autobiography Smith reminds us in Subjectivity, Identity, and the Body that we all carry a history of the body. She asks us to consider whether the body is

“…a source of subversive practice, a potentially emancipatory vehicle for the autobiographical practice, or a source of repression and suppressed narrative.”

Thinking our way through this is like going through a minefield of mindsets that can make each of us into a non-person, in a no-space except for official space. As in my early train ride headed south, mentioned in Astra’s story, bodies moving through time and space learn things, construct meaning. Nancy’s body moving through time and space informs us. Our bodies are not simple abstractions of our current theories but are embedded in the immediacy of everyday lived experience.

How does this woman transcend her experience of violence, put some reasonable order to it? Will she be able to make room for the violence, reconstruct a life story that has meaning to her?

Through every difficult emotion, she sits erect, spine straight, eye to eye with me. Mascara, eyeliner, eye shadow, and rouge all blend subtly and frame her large blue eyes. I remember now that the dancer knows how to do make-up, and how to hold her body.

Remarkably, she decides as early as this first session together to try not to focus on her losses. “My inner sense tells me that it is going to raise my level of anxiety and emphasize my limitations if I focus too much on these things,” she tells me. I understand this as her attempt to maintain a homeostasis, a balance, as she works her way through the losses she is experiencing. She has a way of knowing, not yet known to me and not yet named by her, that this particular strategy works best for her in maintaining her bodymind balance.

At different times our process reflects a mix of emotion, reflection, and judgment. Sarah Ruddick calls this triad “maternal thinking.” Like all modes of human thinking, it has its own logic and interests—in this case, the preservation and growth of one’s child.

How do I as Nancy’s therapist support the virtues of motherhood, such as honesty, justice, wisdom, faith, and courage, and at the same time not perpetuate the myths we have been taught that it is a woman’s “natural” place to care for and nurture another? Knowing at the same time it is a response we all have. How do I do this and at the same time not repress the maternal in each of us?

I engage now in what many mothers have done over and over through time. I draw from my own deep well of experience as a mother, as well as my studies and work as a pediatric nurse and psychologist. I cannot, would not, search only for the treatises of traditional ethics based on the thinking and experience of certain men.

She sits back in her chair looking dejected, alone, and tired. Because of her perceptual and conceptual difficulties, Nancy must take in all new information aurally, and she cannot at this time make use of our extensive women’s studies library, particularly, our books on child development. I will listen for what her child’s strengths and resources are, and for what types of help he might need. My mini-course in child development starts.

“Let me try to give you some basic understanding here. A child’s personality is not just a network of predetermined genetic codes, but an outcome of dealing with the challenges and opportunities that his short life has to offer. Alexander’s success in handling this difficult period will depend upon how he has dealt with previous obstacles in his life, his resiliency, his gifts, his ability to cope with newness and stress,” I tell her.

“From what you have told me about him, your son seems to be blessed in this regard. I am of the philosophy that he needs the freedom and flexibility to find his own novel solutions within the context of your loving family and this loving community. I am in favor of giving him a wide range of options, especially during these times of unusual stress.

“As a young child, Alex has a limited ability to understand people’s comings and goings—who is doing what, where, and why. He will need your help with this. Keep him informed about your comings and goings.

“The tempo of your son’s routine has been disturbed, his unique mother-son rhythm is absent. He will have difficulty conceptualizing linear time. It is a confusing period for him, and the fear of further loss is ever present. Alexander has an advantage in that he has been with grandparents he knows, but he lacks the ability to be ‘time wise.’

Thoughtful silence, then Nancy picks up the thread. “I am feeling so guilty that I still am unable to pick up my son or read to him. I’m physically ill and scared.” Her body seems to disappear into the chair. “What does it all mean? I feel guilty, too, that my parents have moved in to help me, and they’ve just recently retired. They are now thrust into the unexpected, stressful job of caring for me and my son.”

“Look, as a mother myself of adult children and thinking about my own life experiences I’m sure that your parents are grateful that you are alive, and I’m sure that they feel a need to help you. It’s a specific action they can take as they deal with their own anxieties about your health.

“To have a feeling of competence—of feeling creative, of being able to express myself. Since the shooting, I have a lot of self-doubt.”

“Yes, I understand, but don’t forget—it wasn’t just this massive trauma. You aren’t only dealing with the physical injuries; there was also an emotional regression. You experienced an automatic biological response to a threat or catastrophe. Before the shooting, you felt that you were an adult human being, safe, with freedom and choices. At the moment of the shooting, you felt like a frightened child or animal who wants to retreat. The shooting has brought up the archaic fears we all have as children.”

“Exactly. What about work? What can you handle and not handle?”

“I’m looking for my strengths, and other people are trying to protect me. Here I am doubting if I can function, and other people won’t even let me try. The other night when I was alone in my bedroom, I started screaming. ‘What did I do to deserve this? Who is this man who fucked up my life? What right did he have to impose this life on me?’”

“Good. Finally, I hear your anger! I was wondering where you had hidden it!”

Nancy continues, “I want to say to people, I need you to trust me, but tell me if I’m screwing up. Don’t try to proofread me all the time.’” Her face is a study of both rage and despair.

“I understand. The shooting has set off a lot of other people’s fears. They don’t know what to do with that. You will have to let them know what you are experiencing and what you want and need.”

**********

Today on my lake walk, through my Nancy lens I see on the shoreline one huge ashen gray tree uprooted from the earth and toppled over at an oblique angle to the water. I see what looks like a woman’s leg jaggedly torn from the hip joint. Its oversized foot is half submerged in the water. These lakeside artifacts are all I can summon up in my consciousness today.

Several months after the shooting Nancy decided to return to her real estate work part time. Today she comes in feeling depressed and discouraged. “I resent and am frightened about my loss of personal power. At home and at work, people are constantly doing things for me.” As a self-described “doer” and “caregiver,” she finds this dependency on others unacceptable.

“I feel like a fat old lady burdened with a toddler,” Nancy says. “And I have been on a feeding frenzy. And on Father’s Day, I really missed Ed.”

The cultural devaluation of women as mothers, ageism, and the negative views toward an imperfect, injured, and wounded female body all meet today in this session and are a heavy burden to her soul-work.

Her loneliness, her lack of intimacy, the prolonged burden of the trauma itself, and her unresolved grieving for the loss of her husband leave her extremely discouraged, fatigued, and vulnerable.

***********

As Nancy and I get to know each other better, it becomes clear to me that she has a considerable number of layered, complex life experiences to draw from. I learn how much she trusts her intuition, or inner vision, as a way of informing herself—much more than she herself has realized. She often refers to her gut feelings and makes decisions based on her “body sensations,” as she calls them.

In a personal-growth workshop she took before the shooting, Nancy’s Dancerself responded to her instructor’s statement, “Trust the dance.” Neither of us is fully aware yet how much her way of being in the world is born from her trust in the dance.

She sighs deeply. “I have always doubted my intellectual abilities. I always felt there was very little I knew. What’s going on in my brain right now makes that even more real. You see, I completed a four-year dance program in two and a half years on a scholarship. I feel that I lack a well-rounded liberal arts education, even though I went to a well-known liberal arts school.”

“What do you feel that you lack the most?” I ask the woman dancer who has used her body in time and space as an instrument of knowledge.

“Well, I believe that you have all the answers already, your own inner wisdom. You just have to ask the right questions. Well, let me modify that. You have to ask the right questions of the right person.” I smile.

“That’s it. I wouldn’t know where to begin and what would be a right question, or a good question.”

“Let’s put this on hold for a little while, but I think my associate, Betty, can help you with this dilemma. She’s the philosopher-in-residence here, and her Big Maps are much larger than any psychology maps. She can help you understand more about traditional categories of knowing if you want.”

“I think so.” I challenge her, “Let’s be brave and try. I understand your dilemma since I had a similar yet different problem in my doctoral studies. I had not been required to take any graduate courses in philosophy. Therefore, somewhere along the way, I felt I lacked a solid grounding in the general field of philosophy, which embraces basic themes and questions about reality, truth, and value. I realized that these themes and questions were at the heart of my work with women. For that reason, I asked Betty if she would join my doctoral committee.”

“A number of my friends have taken courses with her, but I don’t know her personally.”

A few weeks later, Nancy decides to take the challenge to work with Betty.

Ways of Knowing

The outer room now takes on the mood of a loving classroom. The large easel pad is ready. The lights are somewhat dimmed. We sit in a Circle of Knowing Women.

”So at the same time that you are struggling with a trauma to your body, your spirit is also housed there in every cell and every space between the cells. I understand that Judith has been working with you to give voice to your experience, and in so doing, then how do you create or structure some meaning for yourself? How do you keep your human spirit alive and well? And what kind of relevant knowledge or information do you need to help you? Do you agree with that short summarization?”

“Yes. That’s just about it, but I’m not sure about the courage part,” Nancy answers.

“Well, I am,” I interject.

Nancy returns to the theme that troubles her. “Well, I don’t know what knowing is. I rushed through this liberal arts college on a dance scholarship in two and a half years. The problem is that I mostly danced my way through! If I’m honest with myself and with you, I feel really stupid. And I have a question … if I can frame it. How do I get to know what I know? And I’m not even sure what I am really asking for here.”

“I understand—you framed the question very well. Many women come here with these kinds of questions. That’s where my work comes in. Let me draw something for you on the easel. You don’t have to copy these because I have made out these cards for you to take home.”

“I don’t think I could take notes right now anyhow,” Nancy reminds Betty.

“I understand.” Betty makes a large pie-shaped diagram and labels the three sections. “There are three basic ways of knowing, at least as far as we know—rationalism, empiricism, and metaphorism. Each of these represents a legitimate approach to reality. And there are different criteria for evaluating each approach.”

The seasoned teacher who has worked with more than one anxious student in her classes stays with Nancy. ”That’s okay. I understand. These are still new words for you, and the ideas or concepts behind the words may also be new to you. Just stay with me for now. Try to stay open to these new learnings. If you are having a problem with forgetting or not comprehending some of the words you used to know before the shooting, we can find this out together and help you. I want to introduce you to some ‘Big Maps’ as Judith calls them. And don’t forget we can meet for extra sessions on this.

“Second, there is empiricism or sense knowledge. Empirical knowledge refers to knowledge founded on experience, observation, facts, sensations, that is, concrete situations and real events.

“Third, there is metaphorism, which claims that knowledge is dependent upon the degree to which symbolic or intuitive cognitions can lead us to universal truths. The cognitive processes involved in metaphorism imply a more imaginative- creative mode of knowing than is implied by rationalism and empiricism. Greater overtones of emotion and deeper levels of consciousness are also implied.”

The woman who felt scared and stupid minutes ago now engages in a relaxed three-way exploration with us. She is silent for a few minutes and then says, “Judith, do you think my experiences with dancing fit the second category? I see now that even though I danced my way through college, I was still learning to be more aware of myself and the world around me in these different ways of knowing.”

“Yes, I think you are right on. You have also already made many rational decisions concerning the course of your healing and trying to integrate the experience into your ongoing life.”

“No easy task,” adds Betty. “You are a dancer, and the senses played an important part—the visual, auditory, and other senses—as you created your choreography. Regarding the third way of knowing—the intuitive, metaphorical, and symbolic—as an artist, creating new choreographic forms, you certainly must have tapped into your vast resources of intuitive and symbolic knowing.

“Besides your personal use of the modes of knowing, when you were in college, you were exposed to the various academic disciplines. The sciences, the arts, and the humanities in which different modes of knowing were favored. For example, if we want to know about nature, we can deduce that there is order and pattern from our sensory awareness of the natural phenomena around us. We can also create symbols for nature and the natural processes, such as nature as a great machine, or nature as a living organism.

Betty continues, “Each of us, as human beings, utilizes these processes of knowing. Furthermore, none of these ways of knowing operate independently of the others. We do not think independently of sensory input and symbolic and intuitive processes, nor do we use our senses independently of intuition and clear reasoning. As women, we are often led to believe that a certain way of knowing is more valued in society; for example, our sciences are valued more than our art or poetry. Each woman, however, is capable of being a giant beacon herself, expressing her understanding in many ways, as you do with Judith here in therapy.”

“I need to think about this. There is an awful lot to think about.”

I’m starting to worry, are we overloading her?

Then Nancy turns to me, the other mother in the room, and says, “I was thinking about being a mother. I think maybe I draw from all of these areas.”

“You are right on, and probably some of the ways that we mothers have not named yet and have not valued yet.”

I look at my watch. “I hate to say this but our time is up.”

Betty takes out some brightly colored, laminated index cards that she has prepared for Nancy. “Why don’t you keep these? We can follow through on these again if you want to.”

*********

**********

Nancy comes in today dispirited because a date she was to have had with a man was canceled. “I feel like a ‘third wheel’ now.”

“What script did it set off in you that makes you feel so down about the date being canceled?” I ask her.

“People? —or men?” I challenge her. “I am not trying to invalidate what you said, and I understand that your thoughts and feelings here are common to a major trauma, but I want to appeal to your basic intelligence and to expand your thinking.

“Well, I guess that’s one way to look at it!”

“Well, it’s the only way to look at, and it’s also true!” I tell her. “I know that this is a time in which you’ve had a loss of faith about the world and your place in it. Hang in there.”

**********

“What’s this about for you? I’m curious.”

“I’m surprised about this. What about showing your body when you were dancing? How is this different?”

“I guess I was so skilled, and there are always ways you can dress to make your body look longer. In dance you are holding your body in. I grew up in a studio, so I am comfortable in that enclosed environment,” she responds.

“I know no woman—virgin, mother, lesbian, married, celibate—whether she earns her keep as a housewife a cocktail waitress, or a scanner of brain waves—for whom her body is not a fundamental problem: its clouded meaning, its fertility, its desire, its so-called frigidity, its bloody speech, its silences, its changes and mutilations, its rapes and ripenings. There is for the first time today a possibility of converting our physicality into both knowledge and power.”

“Wow. That speaks to me.”

We sit in a profound and knowing silence.

Laying a Life to Rest

At our next session, Nancy tells me the following vignette:

“I feel really good about this. I had packed up all of Ed’s things into one box after he died. I didn’t want to create a shrine to him, so I was selective about what I kept. You know, things I thought were representative of him and for Alex to have someday. Well, with Alex, I took the box from the basement and took out each thing and put it into a special Victorian trunk that I have always liked. Alex asked me a lot of questions about when is Daddy coming back and things like that, so we had a chance to talk about things. Now I feel there is a special place in my house for Ed’s things.”

“You know, it has always been women’s way to take everyday life events and make them sacred, to ritualize the sacredness of life and death as well. It feels to me that this is what you were doing. You set aside time with your son to remember his father. To make a sad event sacred and special.”

I had been reading The Woman’s Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred Objects the night before, and I share a passage with Nancy. In it, Barbara Walker writes,

“No object or symbol is sacred in or of itself, as an inherent quality. Sacredness comes only from the attitude of people toward the object. A thing becomes holy because of the way people handle it or talk about it, teaching themselves, each other, and their children to feel proper awe in its presence.”

“I appreciate your thoughts, because this is how I know whether my therapeutic interventions are useful.”

Nancy continues, “I want to share with you what’s been going on in the past few weeks. I’m feeling really good today, but it seemed to start on my birthday—this downhill slide, this dissatisfaction with myself. There was a period of time when I was totally exhausted. I had this depression, and my self-esteem was zero. I feel that I went through all this stuff and I really... and then I woke up and said, ‘Why did I survive? Why am I here?’”

“What was your mood? Can you describe it?”

“I was sarcastic, quick with people, bitchy. I was bottom-line unhappy with myself, my life, and everyone around me. That stayed with me until yesterday, when I was at a family reunion of about forty-five people, and I was inundated with admiration for my courage. There were lots of tears and love, and at the end of the day, I had no choice!”

“You had to feel better despite yourself.” We both laugh.

“Yes,” Nancy agrees, using her body as a compass. “I have this edge of impatience. I feel like I’ve gone from this fetal position to a toddler in a playpen with my vertigo, then walking, and now I feel like I can’t run fast enough.”

“A kind of blankness and silence in which to further breathe and heal?”

“Yes. That’s it, I guess.”

**********

The next week, Nancy is feeling even less good about herself.

Her struggle for meaning and purpose continues. I say. “The questions you are putting out are not that simple. They are complex, philosophical questions about the meaning of life. Be patient. You need time.” Nancy is challenged by her brush with death.

“Well, I’ve been thinking about this. I’m very audience-motivated, and I’m not being viewed now. In looking over my life as a dancer—from three on—I never spent time in the studio alone. I would create on the spot in rehearsal. I can’t think of a time in my life when I’ve been alone to think, process, or create. My best thinking is happening here in this office. When I’m alone, it would be the last thing I would do, to sit and think. I’m more apt to do the laundry.”

Though Nancy is saying something important here about her thinking process, I decide to mark this as another side note and leave it for now.

“About your body, I want you to know that I experience you as having a strong physical presence—the presence of a singer or dancer, a performer who uses her body. I get a sense of people’s energy as we work. You project an unusual amount of energy.”

**********

‘Let me respectfully remind you: Life and death are of extreme importance. Do not squander your lives.’

“Is this something like you were feeling?” I suggest.

“Yes. I often find myself thinking what is my life all about? Is this all there is? Then there are other times when I just withdraw. No thoughts are there, and I don’t know exactly where I am.”

“If it’s okay with you, I’d like to shift and talk about Ed now. I really know very little about your life with Ed, and, until I do, I may not be able to help you in this area, to understand some of the structures on which you have constructed your life story.”

“Would you say things in the first person, please?” I remind her.

“You felt the responsibility for the relationship working? This is an important women’s issue here, that if you waited long enough and did the right things, everything would change. You were always imagining his potential. Is that right?”

“It seems to me that because of your inexperience, you had not considered that Ed was probably already using drugs around the time of Alexander’s birth, if not earlier. The drastic change in his appearance, his verbal abuse, and other oppressive behaviors would indicate this. Drug use would also explain his many disappearances and lack of availability and his eventual unplanned death,” I explain to Nancy.

“What did you feel while you were talking just now—what emotion?”

“Anger! I never told him how angry I was. It was so hard. Not just adjusting to being a mother.” Nancy’s voice slows and softens, and she begins to cry again.

“So your feeling of being abandoned, and your loss, started long before he died.”

She sobs uncontrollably, and I hold her.

Mournful silence settles over the room.

“I’ve thought about this over and over. Maybe if I hadn’t set those strict rules before I was married about no drugs and alcohol, it would never have happened, though it seemed like a wise idea at the time.”

“Look, it’s important to understand that it seems that Ed couldn’t make a commitment to you. He still had to deal with the problems and monsters in his own life. I don’t think that what you requested of him had anything to do with his leaving this earth. It’s a lot more complex than that. You are giving yourself too much credit for having that much power over another individual’s entire lifetime of experiences. You carry much too much guilt around this, I think.”

“But it’s not grandiose,” I postulate. “We have to live in the world as if when we do good, we will get good back. But then we have this dilemma. Where do we make room for an experience like the shooting? Or Ed’s behavior toward you? And what is the alternative to putting out our goodness and caring for the world? What other choices do we have?” I continue, “As a white, middle-class, heterosexual woman, it is difficult to conceive of a world in which anyone would want to hurt you. Many women of color are far less likely to be so naïve and trusting in a country in which racism is so prevalent. The same is true for women who must live in high-violence neighborhoods.

“What in your personal history or belief system would allow you to believe that a man who has a gun does not intend to hurt you, that a man who says he is a con artist will not con you?

“The particular reaction you and Alison both had, that you thought you wouldn’t be hurt, was a great challenge for me—to stay with you, where you both were in your own process about trusting him, despite the fact that this man was pointing a gun at you. And, from where I sit, working with so many women, I’m thinking, God, look at the data! The evidence is overwhelming that these crimes are done by men. Yet at the same time, I understand your terrible dilemma. How do we get back our faith that the world is okay, a safe place for us?”

I look at the clock and add, “Before we stop, I’d like to know what particularly stands out in your mind about today’s work.” I leave the room for a moment to let the next woman know we are running a little late.

We have covered a wide range of subjects and feelings in this session. Often I do not know what a woman carries away from the session that is particularly useful, what new concepts may have come up. In addition, I must constantly monitor the effects of my interventions on the therapeutic process. When I return to the room, Nancy has an answer.

“The idea of abandonment. That’s a new idea for me.” She reflects on this for a moment.

“This has been a particularly emotional session. What do you need from me around this idea of abandonment?”

“It is, of course, symptomatic and typical of your posttraumatic stress disorder. You have been lonely and scared, and you have worked very hard to stay focused on your healing and caring -for Alexander. I think also you feel isolated. You have already indicated that you have been a very public person before this isolation. I don’t really know what you have experienced after Ed’s death before the shooting. We have only begun to talk about unresolved issues with Ed,” I tell her.

“He didn’t come to me about what was going on in his life, and I feel responsible, given his addiction and my total ignorance of alcohol and drug addictions. Looking back on it now, I realize that there was a pattern. Every year, for example, he had elective surgery, and he would then get prescription drugs. He said himself he was a real con artist. But I didn’t believe it.”

“What did you get out of your relationship with him?”

“You got a lot of support from him. No matter what, he was there for you. He would stop or cancel an appointment for you so you could spill your guts out,” she explains.

“Would you say ‘I’ instead of ‘you’?” I ask Nancy again.

“When I was getting massage work once, I was asked to define independence. My

“Who was your first rock?”

“Probably my mother.”

*********

Today, at my request, Nancy brings in photos of Ed. She has been thinking intensely about him, their marriage, her low self-esteem, and Ed’s criticisms of her. She is feeling both guilty and sad. I see photos of earlier happy times, full of the ideals of romantic love and expectations.

She puts down the photos in her lap. “I was feeling this low self-esteem and a bad body image and feeling really nervous, thinking about the first time that I go out with someone else, you know, on a date. I’ve been thinking about Ed a lot. He was constantly talking about my weight. I always thought it was me. Sexually, I started not taking care of me, my body. Instead, I was always taking care of him.”

“So, you thought you were the problem, and you thought you had to solve the problem.”

“Yes, and I don’t want to repeat that with the next person. I want to love my body however it is. I need to be able to initiate it first, and I need to be comfortable in a receiving place. It was always for Ed, not for my own needs.”

“Your need for intimacy and touch versus sex for its own sake or for his sake. You must have been pretty lonely.”

“I didn’t name that. There was room for me to express intimate things, but he did not like to hug or kiss. He did not like to be comforted physically—no back rubs, no hand holding.

“I was a classic enabler, I think.”

“Stop right there. That implies again that you were the problem!”

**********

“That’s amazing!”

“I have been feeling really sad about Ed. I feel he participated in life, but he didn’t live life. He was a character in a script in a movie. I was the right actress for the role. He was concerned about how things appeared. There was no core self to him. He learned what to do by watching the scenes of life.”

“But now you understand that the struggle was that you wanted more, to live more fully, to be more deeply engaged in life,” I reflect.

“You were objectified in that relationship, treated as an object. You didn’t feel entitled to anything more or better, and that’s what we have to examine. This is an important women’s issue here. We need to examine where you learned these things, that this kind of behavior is acceptable, starting with your family and then examining the culture at large.”

“Well, I think that most of my intimate relationships with men have been based on me putting up with things because I believed I didn’t deserve better,” Nancy speculates.

“Did this happen with your intimate relationships with women?”

“No, just the opposite.”

“How do you explain this?”

“I almost always felt more knowledgeable with the women. The women were less experienced in life than I was. They were mostly my students. When I was 30, I went out with a man for four years. I was always asking him why he went out with me. He was so much brighter, I thought. I think that’s why he left. He got sick of hearing me! I don’t blame him.” She’s able to laugh at herself now.

“Or maybe he left because he realized how bright and gifted you really were—even if you didn’t!”

“Start thinking about it if you’re coming for therapy here!” I tease.

“I have had a number of other adult relationships, but I still do not have a sense of what would be an equal, intimate relationship between a male and a female.”

“Not an easy task. There’s so much working against this.”

“I wonder what would have happened if Ed hadn’t died?” She leaves her own question unanswered.

“You know, Nancy, we mourn not only what we had and lost, but what we didn’t have in the first place.”

“The last time I saw Ed, at the wake in the casket, his sister was hugging him and touching him over and over. I thought how he would have hated that, being touched. I went to him and kissed him and told him I forgave him. And at that very moment, I had this fleeting but greater understanding that he did the best he could, and I forgave him for his weakness and for the fact that he wasn’t what I needed. But I still get so angry.”

“Maybe the struggle here is more about forgiving yourself.”

“How can you help someone who doesn’t ask for help? And when you helped him in the way he wanted it, it meant giving up your own life. Is it fair to trade off one life for another? It’s omnipotent of you to think that you could do all this for Ed.”

“I used to feel, if he could just let go.... But if he let go, there was nothing there. No script. He felt absent, empty, a nothingness.

“Look. This is your journey now. This is about your healing.” I point to the poster on my wall that reads, “Love is what we’re here for.”

I say. “I will support you here. Your mother gave birth to you, but this is about your own rebirthing.”

**********

“Synchronicity is a descriptive term for the link between two events that are connected through their meaning, a link that cannot be explained by cause and effect…. An actual event coincides with a thought, vision, dream or premonition.”

Bolen goes on to explain the important differences that exist between synchronicity and causality:

“Causality has to do with objective knowledge. Observation and reasoning are used to explain how one event arises directly out of another…. In contrast, synchronicity has to do with subjective experience…. The timing is significant to the person, for whom the inner psychological premonitory feeling was in some unknown way linked to an outer event, which then followed.”

Based on a conscious choice to face danger and to work and live through it, and her trust that these synchronous events have some as yet unexplained meaning, in August, Nancy and Chuck decide to travel to Sedona.

Of Vortexes and Butterflies

“We arrived in Sedona, and I had exactly the same experience as in my vision. We were driving down the road, approaching Sedona, and there was a clearing. It opened up, and you saw these magnificent red rocks jutting out of the earth. I got out of the car and just sobbed. Something about this vision moved me like nothing else I have ever seen, including the Grand Canyon. This place spoke to me.

“We checked into this rather drab little motel room, and I didn’t know what to do. I thought, ‘My God, I have to start this thing tomorrow, the first day of the new moon.’ I said to Chuck, ‘What are we going to do?’ We went to the Chamber of Commerce and I picked up this flyer that described the New Age Center. We both looked at it and said, ‘Let’s go.’

“It was five o’clock, and they were just completing this New Age fair. All these huge tables were covered with crystals. People looking like old hippies were all over the place. I said, ‘I don’t belong here, this isn’t my kind of scene.’ So we just sort of stood there for a minute, then, out of this back room, I swear to God, this woman walked into the room, looked at me, and came directly toward me. She was wearing a full-length white caftan, had silver hair and piercing blue eyes, and was wearing a huge cross around her neck. She walked up to me and said, ‘I can help you,’ and I immediately burst into tears. I said, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing here, I have come clear across the country. I had a vision of Sedona, but I don’t know where to start.’ She said, ‘Come with me.’

“We went outside and sat down, and she held my hands. She said, ‘The reason you are here is because you need to do some healing.’ I started crying again, and she asked me what hurt. ‘My husband died in September, and I got shot in February,’ I told her. And she said, ‘You have come to the right place. This is what you need to do. You need to be here for four days.’ I said, ‘Oh, my God, we had made plans to be here for four days.’ She said, ‘There are four vortexes in Sedona; they are the four places of magnetic energy.’ She went to get a map, came back and showed me which direction to go. It was the reverse order of how the map shows tourists to do it.”

The vortexes Nancy refers to are known sites of highly charged electromagnetic energy, which many consider to be characteristic of mystical or sacred spaces.

Nancy continues, “The woman told me, ‘The first thing you are going to do is to go to Oakley Canyon. You need to bathe in the water. It has incredible healing powers. It will help you for the rest of the trip.’ I felt tingly all over. I looked at Chuck, my pragmatic IBMer. I said, ‘What do you think?’ He said, ‘I think she knows what she is talking about.’

“The woman told me Chuck would be my guide. I always thought I would find these spots. I didn’t know that Chuck would.”

“But you had already picked him as your guide from the other vision, right?” I clarify.

“Yes,” Nancy tells me.

“You were following the map?” I ask her.

“Yes, we were just walking down the river bed. Chuck said we had to cross the river. We crossed the river, got to the other side, and Chuck told me we were going up a steep incline. We started climbing, and he kept saying, ‘Go slow, just pace yourself, one step at a time.’

“We reached a small ledge, which was in total shade. Chuck said, ‘This is where we need to be.’ I disagreed, and just at that point, the yellow butterfly dived at my head. Chuck asked me to look up, and about thirty feet above us, the rocks went straight up and created a V. At the point of the V was high noon. The sun was moving in. We were soon bathed in sunlight.

“On the second day, we climbed the second vortex. When we started out, it didn’t feel good. We could hear power drills. We always had the experience that we were in the wrong place. We walked two hours in extreme heat. I saw this precipice, and I said, ‘I think we have to go up there.’ Chuck answered, ‘I don’t think so,’ and I said, ‘Yes, this feels right.’ We walked up a steep incline, got to a ledge and looked down. There was the yellow butterfly.

“As we were walking, Chuck said, ‘We are going to go to the top of that mountain.’ I said, ‘No way, let’s keep going. I think it’s up further.’ The butterfly went back to where Chuck had wanted us to go. We stayed up there for a little while, then both of us agreed that it was the wrong place. We climbed down, and followed the butterfly back. We walked through a prickly thicket to reach the base of a five- or six-hundred-foot peak. I was petrified. It was totally vertical, and he kept pushing me. At one point, I stood there crying, saying, ‘I can’t do this. It’s too hard.’ But Chuck told me I could, and we reached the top.

“It was a three-hundred-and-sixty-degree, panoramic view. I took a piece of stone from each vortex, which I still have. I looked out over one place, and there was this rock that came out, and I saw in my mind an Indian standing up there in original clothing and everything, just looking out.

“How did you know he was a warrior?” I ask her.

Nancy is anxious to continue her story. “My last vision was of a silver-haired man with big blue eyes. Chuck said, ‘Nancy, it’s high noon,’ and the vision suddenly stopped. In this entire experience, my mind felt like I was on drugs or something. It was intense, full of color, and vivid visions.

“Was it a real butterfly or a vision of a butterfly?” I ask.

She reiterates, “They were all real butterflies. We never saw any others except at the vortexes.”

At this third vortex, Nancy had another vivid experience.

“When Chuck returned, the lizard left. I told Chuck that Ed had been with me. Chuck played psychotherapist. He was wonderful. He has known me for a long, long time. He told me some really hard things, he didn’t pull any punches. He was just great. We both cried, and, as we stood up to leave, the butterfly came back. We left, so that was the Heart part of the journey.

“On the fourth day, we reached the fourth vortex, which I knew was going to be Spiritual. Chuck discovered a crevice in the rocks with a lone pine tree leaning out. ‘We need to go up into that,’ he told me. The spot was like a cave. I put my crystals out and also a small container of ashes that someone had given me when I was in the hospital. They were the ashes of a yogi teacher.

“We sat there for a long time,” she continues her story. “Wait, I have to back track. Before we got to the cave, we went to this one place and I said, ‘I think this is the spot,’ and Chuck said, ‘No it’s not,’ and he said, ‘Let me go over here and see if I can find it in this direction.’

“I was standing there, and all of a sudden my legs started shaking, and the wind started blowing real hard, and I heard a voice. I thought it was Chuck, but I looked around and it wasn’t. It was a woman’s voice. When Chuck reappeared, I started speaking what the voice was saying to me.

“We continued to another crevice. After Chuck read for a while, I told him, ‘You have to stop reading and be quiet.’ I took out the ashes and held them for a long time, then lifted up Chuck’s shirt, put the ashes on his heart, and on mine, then on my mouth.

A sudden gust of wind scattered the rest of the ashes everywhere. I gathered up my crystals, selected the stone to bring back from the fourth vortex. Then I felt my journey was complete.

But she hasn’t finished telling me of her spiritual voyage. “We continued to the Grand Canyon, where we spent time sitting on the rim of the canyon, talking about the meaning of life and time. We were also understanding that when we came back home, we would need to resume our lives even though we felt sort of purposeless in some way, you know, making money, buying groceries…

“All these things felt kind of silly, but we also recognized that people need to do them, to fill our life with things that feel important, because if we didn’t, we’d probably go crazy with our insignificance, in the global vastness of everything. Not only landscape vastness, but spiritual vastness and planes of existence, and all those things. Also recognizing that even though we are here for just a short time, it’s not about just us being here. It’s about what we pass on, and how that gets channeled into millions of different factions.”

The Sedona trip has changed Nancy’s life in a fundamental way.

“I feel very grounded, very energized, very healed and whole. I always listened to stories like this with a grain of salt, and I still do, even though I experienced it. My logical brain still says, ‘Well, somebody must have been hiking up there and the crystal fell out of their pocket, and there are probably hundreds of these butterflies, and it just happened. But we did see the butterfly as we left the crevice,” she reflects. “I looked down, and the butterfly was circling around. I said good-bye to it, and it flew off. I don’t want to live there, but I feel that Sedona is a place I will need to go to, maybe every five years, and take Alex.”

“A pilgrimage?” I asked. “I was trying to remember if that was the word you had used, when you said it wasn’t a trip, it was a…”

She drifts off into another state of consciousness. “I think of the desert as infinity. I can do anything there. It made me feel bigger than life.” Long pause.

“You know, the desert has always been associated with finding or having a vision,” I suggest. “I believe that what you are describing is a transformative experience. With transformative experiences, there is a qualitative shift in one’s state of consciousness. The world is never experienced in quite the same way again.”

**********

In our next session, Nancy sits forward, upright in her seat, her body reaching out to me. “Did you understand last time the power of my Sedona experience?”

“What is the difference between the two words for you?” I question.

“A journey is chosen. With a mission, I don’t have any choice. There is a clear purpose to a mission. I am compelled to do it.”

She responds, “It’s funny, I have never been a seeker of self-knowledge. I mean, I never examined certain planes of being. I’ve never been interested in holistic medicine, energy, and other ways of healing the way that Alison studies these things.”

I encourage her. “Different knowledge can be gained from different states of consciousness—what you call ‘planes of being.’ Whatever your approach has been, you have given a lot of energy and talent to this community as a teacher and healer in the performing arts. A number of women with whom I have worked over the past few years told me about how you arranged work-study scholarships for them so that they could study dance with you.”

“I think my way is intuitive,” Betty’s student responds.

“Yes, I think it is one of your ways. You had the core, the transcendent experience itself,” I explain. “You weren’t looking for someone to tell you something. The only way you could have those visions was through yourself, through your own exchange of energy with the environment.

“I was struck by what you said about we are just little specks in the vastness of Mother Earth. I know what you mean. If you examine the human capacity to have the experiences you had, there is some reason to know that we’re but specks, yet to transcend that state. I feel so enriched by the gift you brought to yourself and to me today.”

I have a strong desire to read her something by Barbara Walker that I read a short time ago:

Psyche was the Greek word for both ‘soul’ and ‘butterfly,’ dating from the belief that human souls became butterflies while searching for a new reincarnation. The mythical romance of the maiden Psyche, beloved by the god Eros, was an allegory of the soul’s union with the body and of their subsequent separation.

But I do not read it to her because for Nancy her mission to Sedona feels whole and complete. This story belongs to Nancy, not to me.

“Here, this is for you. I bring you the energy of Sedona.”

The crystal sits on the Divination Table.

Staying Alive

She begins her narrative, “A couple of things have happened that have sort of shaken me up, and I want to talk about them. I came home from Sedona with what I call my ‘Sedona high,’ but two things happened. I was in a car with a friend and had a near accident. I did not see some cars parked to the right of me and almost hit them. Cars are not usually parked in that place, so I didn’t expect them to be there. My friend screamed at me, and then I saw them and the accident was averted. The cars fell right in the path of the blind spot on my right side.

“Then, the second one was late one night when I was leaving Alison’s house. As you know, there are many dirt roads down where she lives. It’s really rural and isolated. Well, there was a T in the road and then a sharp curve to the right.” Nancy’s whole body is animated as she uses her arms to show me as graphically and spatially as possible what happened. “Well, I didn’t see the curve, went straight ahead and almost ended up in a ditch with an oncoming car approaching me. I was able to get the car in reverse and get out of the ditch before the car approached me. It was awful.

“So you’re getting used to the blind spots now. I think you couldn’t really deal with the immensity of all of this a few months ago because you had so many other losses to deal with. I have been concerned about your vision and was somewhat surprised that the ophthalmologist let you drive. I thought you and I felt you needed more time for both your tissue healing and your psychological healing, as if we could really separate the two.”

“Well, he has never been open to expecting my vision to be any better. He thought I would be legally blind, but I surprised him.”

Nancy heaves a long sigh. She continues to amaze me with her resolve and her problem-solving skills.

“Let’s back up a minute. How did you react to what I said about your vision and driving? Were you angry?”

“I don’t know if I’m annoyed or angry. I guess I got defensive and just blocked what you said. I don’t want to get into any accident, and I certainly don’t want to hurt anyone.” She pauses. “If I get too cocky, it takes me down a peg or two. I need to be more conscious and more aware.

“I feel now that in accepting my disability, it doesn’t mean that I’m not a whole person. It means I’ll just have to take more action around it.” She pauses again. “The old family tape is I’m too ‘cocky,’ but I just need to not be so selfish when I drive.”

“I’m asking you on behalf of yourself as well,” I explain.

“I know, but you see, I have such a strong sense of being protected. It’s like at the first vortex in Sedona. There was a scorpion there, and I said to myself nothing will ever happen to me.”

**********

Our work is particularly uplifting for both of us today. Nancy is elated.

“Guess what? You won’t believe this. I can now read much better. But some words still don’t make sense to me. It’s like I have never seen them before, but I’m feeling much less limited by it, more challenged by it.”

k originally, because it was so frustrating, I would give up. I was saying to myself, ‘This is too hard, this is something I am going to have to live with the rest of my life…’ And now I’m saying, ‘This is just another challenge, Nancy. You can overcome it.’ I need to read more and more, every day. That’s how I’m going to overcome it. That’s what I think.”

**********

It is a hot day in August. My voice leads. “After you left last week, the woman who was scheduled immediately after you said to me, ‘I would like to have that woman’s positive energy. I really picked up her energy as she came out, and it felt very spiritual.’”

“Did she notice me because of how I dressed or how I looked?”

“No, she said it was an unusual energy field. This woman herself lives in a spiritual community. She is a Sister of Mercy, and she picked something up in you. Since she is legally blind, she did not experience you by seeing you. I decided it would be okay with you to tell her you were one of the two women who was shot and had recently been on your own spiritual journey, because you and Alison already gave me permission to do this.”

“Of course it was okay, and that really interests me because I want to tell you something that happened. Last night, one of my friends said, ‘You look so beautiful.’ I said, ‘I feel beautiful.’ Now, even saying those words feels different. If I had said that a number of years ago, I would have said it was too boastful, too egotistical, but when I said it last night, I knew it had nothing to do at all with how

I am excited for her, but I do not interrupt the flow of her narrative. It is as if she knows the other {mumble} of Astra.pg 201

“I am really thinking about this sort of new concept, that is, that we can create our own lives. In fact, taken to the extreme, I could say that I created the shooting, but I don’t believe that at all now. But I do recognize the change in me, given my traditional Christian background about sin and punishment. Now I really find it hard to believe that stuff. I realize I can create what I want now. I don’t want to sit here and sound omnipotent, but I feel we are more in control and can support our lives more than I ever thought we could.”

“I became conscious of the change since the Sedona trip, but I think I have been in some kind of transition since I started thinking about the idea of ‘trust the dance.’ When I took that personal-growth workshop, I asked this person, why didn’t I have a child? This was before Alexander. I was told that I didn’t believe that I deserved it.”

“So not being able to conceive was a punishment of some kind?”

“Absolutely, at least that’s what I thought.”

“You really believed then that some higher authority was punishing you in some way?”

“I see now from our last few sessions that I never valued myself or acknowledged my own success. I thought that my dancing and teaching skills were just gifts from someone else. I managed to ignore or discredit the many hours of hard work that I put into my dancing from about age 3 onward. I thought that it was a natural ability and that it didn’t count.”

Remembering my own childhood as a musician, I have some questions. “What was your mother’s reaction to your dancing?”

“Well, she was highly critical and rarely satisfied. She was also very encouraging. I got support, but I didn’t get applause from her or from my father. As I grew older and switched from commercial to more experimental dance, they didn’t know what I was doing and didn’t support it.”

“How did you know that your mother loved you unconditionally outside of dance? That’s not easy for a child to separate out: loving you, but not your performance.”

“Well, she was always there. She was consistent. She was not consistent in her positive support, though, and I felt that my father didn’t love me for a long time. I didn’t understand until I was about 35, when he had his own life trauma and needed support, and he started opening up and letting go of the macho stuff.”

“So you equate your mother’s love with performing well. The seeming contradictions of both encouragement and criticism from your mother must have been difficult. You equated mother love with performing well?” I repeat.

“I guess I did.”