Sofonisba Anguissola: Renaissance Art and Therapy

The mental pictures, collages, and maps of Astra’s, Nancy’s, Allison’s, Norma’s, and Pat’s stories sit by my side now, along with an ample supply of blank canvasses and papers of different textures, waiting for the images that Clare’s life story will evoke in me.

She is a Sister of Mercy. Forty years old. Small. Dark brown eyes and dark brown, bobbed hair. Thick eyeglass lenses cover her eyes. She looks earthy. Grounded. Her head is ever so slightly tilted to the left side. She writes on the Intake Sheet that she is legally blind.

The shape of her oval face and the form of her soft and slightly rounded body contour remind me of a wonderful oil painting done by the Italian Renaissance painter Sofonisba Anguissola—the one of Sofonisba sitting at her spinet with the haunting figure of her aging maidservant blending into the dark pigments. As with the aging maidservant, an older white-haired friend perhaps in her late 60’s sits today with Clare here in my office in the outer room.

She has an adagio tempo as she walks from the outer room to the Inner Room. She shows no hesitancy, but looks down as she walks.

She sits back in her chair and, with a steady voice, starts her story. At times the narrative is marked by variations in color and tone, but the dark pigments and tone of the Sofonisba oil painting is where I first place Clare on my Renaissance map. Without flinching and with an immediate inner dedication, she fingers each segment of her story slowly, as if it were a bead on her rosary.

“Let’s see. I have to fill you in. It’s now January. Well, in November I had some pain in my left breast. I called my doctor and she saw me right away. She examined me and found some swelling and thickening in my breast. She referred me to a surgeon who examined me and did a biopsy. They both thought the problem was benign. So I didn’t worry too much. Then—you won’t believe this: The biopsy came back positive. I have a malignancy.”

She pauses. The overpowering memory of the unexpected news sits before us like a dark, heavy, unopened package. “Then a mastectomy was scheduled for as soon as possible but the lab work showed that my estrogen levels were high, that’s normal, you probably know, for a premenopausal woman. Well, ovaries are the origin of this hormone, so I had to decide whether to do hormonal therapy or surgery. I decided to have my ovaries removed to control the cancer. So that’s what was done.” Another pause. “The good news is that after this, believe it or not, the cancer cells in my breast and under my arms disappeared on the x-ray. I try to share my life with people so my poor friends got it first-hand because they were right there in the room when the surgeon told me. You can imagine how they felt. I didn’t even cry with that one.”

I take over, hoping to give her a few moments of reprieve. “Well, you were still in a state of shock. Did you feel like you were sort of standing outside of the scene and observing what was happening? It’s difficult for the brain to register all of this at once. It’s all so overwhelming. Is that how you felt?”

“Is that it? It sounds like it. I hadn’t labeled it that, but now I have this bone scan coming up in the spring and I’m really scared.” She sighs. ” I don’t know if I have the resources to deal with that.” I make a side note: Prepare for bone scan in spring.

I pick up her need. “No one should have to deal with this alone. We all have to support each other through times like this,” I tell her.

She nods and pushes on. “Then last June my father died. I stayed at his house for six months and helped him until he died.” Another sigh. Another side note: Recent loss.

“And soon, I want to talk about my friend Marlene. She is unique, boisterous, active, energetic. She is prophetic and ten steps ahead of most people. She has a way of cutting through the muck of life. I miss her a lot. She’s working in Peru.” Another sigh heaps onto the other one. Side note: Another loss?

“So these are the issues. And this bone scan. I feel it could wipe me out, but I feel fortunate. I have my prayers, good energy, I think, and support from my community.” She pauses. “And I have a positive attitude.”

With a smile I hope is not ill-placed, I add, “I would call that the understatement of the day.”

“Another thing. I have always kept a journal, but now everything has stopped. Nothing is flowing. My thoughts are frozen. Just frozen. Everything is frozen. This really worries me.”

“You mean, the inability right now to reflect and to examine the events of the day on paper?” I ask.

She nods. “Yes. That’s it. This is very unlike me.”

“Let’s back up a minute. If am I hearing you correctly, it is not so much that you fear the diagnosis of cancer. That is bad enough, the shock of it, but wondering whether you can draw out the resources from within yourself for this next part of your life?”

“Yes. I feel I’ll have to draw from some place that I haven’t tapped into before.”

“Does this thought feel fearful?”

“Very much so—and lonely.”

“Even in your community?”

She does a shift and fingers another bead. “Yes.”

She starts now with an intergenerational story of her mother and father’s origins and lifetime up until the time she was born. Early on, I understand that this woman sitting before me intends to give me the longer version of her life in order for me to understand the origins of her rootedness.

“I want to tell you about my family,” she starts. “My story begins before I was born...I’m the youngest of nine. I have half brothers and half-sisters and a different father from them. I have a collective memory of my childhood in the context of my parents’ lives; it’s an unusual story. My mother was born in Canada. My mother’s mother died when she was 3. Her father remarried and moved to the States. My mother was a stepdaughter and worked like a horse. She married when she was 18. She had eight children but not a happy marriage. At 38, her husband committed suicide, but the family story was that it was a gun accident. The family was not supportive of her, and she had adolescent kids, so some of the children were put in French Catholic boarding schools and another baby was put in a foster home. My mother then went to New York for special nurse’s training.

“Two of my sisters entered the convent before my mother remarried my father. I was a change-of-life baby and my father was delighted. My mother was happy, but her capabilities for showing affection were sometimes limited. I grew up with four siblings; the rest of the people in the family go in and out of my life. When I was young, I thought if I even talked about my vision problem, gave voice to it, I would be like my father. So I tried not to say I had a problem seeing, because that would make it real.” Another sigh.

Her voice falters now, holding back an inner grieving, mixed with joy. “My father had a Huck Finn existence. He had glaucoma when he was 18; that’s when he started losing his vision. He was left with shadow vision, but he still ran a farm with his brother. My father was a great storyteller. He would tell me about his loneliness, how he would go out to the barn and sense the warmth and aliveness of animals. In the growing season, he would go out to the fields and he told me about the wonderful sense the feel of rain gave him. As far back as I can remember, since I was very little, he told me these stories filled with deep emotion.”

She continues to tell of her early years. “By seventh grade I had no vision in my left eye, and my right eye was not good. I went to Boston and had surgery for my left eye. Later my right eye was removed because the optic nerve was dead. About three years ago, I started experiencing more visual problems. They tell me I have a cataract now. I was extremely frustrated that there will be no surgery for my left eye.”

Without warning, she takes a tissue from the box near her, leans over and takes out her prosthetic right eye. Even though I am a licensed professional nurse, as well as a psychologist, I am not prepared for her sudden anatomical lesson. An early testing of me, no doubt!

The eye put back in its right place, we continue.

“How did you get by in school up until that time? What did you do?” I ask her.

“What I did is I pretended that I could see.” She laughs. “As you might guess, I didn’t have much of a social life in high school. Somewhere in my senior year, I got in touch with my inner spirituality.

“Since my vision was limited, I had to spend longer times reading and doing my homework. I asked myself why was all this happening to me. I started questioning many things at a much younger age than other children. Later, I think I used religious life as a way of standing on my own two feet and not dealing with male relationships, which were a pressure for me.”

“Yes, the social pressures of a bright, female child. How we ‘do’ being female.”

“However, for twenty years I have had just enough vision to get by as a normal person. About three years ago, my vision got worse, and I was told I had a cataract.”

Clare heaves another deeper sigh from the same underground stream.

“I thought about social work school after my father died in June, I went home to nurse him, but I wouldn’t admit I had a vision problem. Even though everyone else knew it, I couldn’t admit it. I researched the problem and found out there were services available to me and instead of feeling diminished, I felt freed. It was a revelation. Then through the Division of the Blind, after they met with me and assessed my skills, I got a job at the Center for Independent Living for differently abled people. I worked for two weeks and then discovered I had this cancer.”

In the middle of the darkness of her story Clare says to me, “Then, all of a sudden a light went on: ‘I’ve really got a problem here. I can’t deny it any longer.’”

“I’m glad for that light because it brought you here.”

“Wait! I’m not done yet! They also told me I have to have cataract surgery soon to my left eye. It’s too much for me.”

Other faces of an extended family join my canvas and a gauze-like white sheet now hangs over it and obscures the tonal quality of Sofonisba Anguissola’s Renaissance map. A cloister, a farm, and the image of a bright female child studying alone slip under the white veil as well.

I understand that Clare and I are making an unspoken contract with each other and that she wants, no, maybe expects, me to be there from beginning to end. And amazingly, at the same time that she is telling me that she has cancer, she adds, “There’s a whole new dimension in me that I want to explore. But,” she falters, “I don’t know if I can handle the future alone. It’s a part of me that remains unknown.”

“So you need someone to journey with you?”

“Yes, I really do,” she tells me.

“I understand. We can do this future together. Create it, refashion it together. Thank you for letting me share this part of your journey with you. I think you’ve come to the right place.”

“Well, I know I have. I hear that you are a feminist. That’s why I’m here, you know.” She manages a grin.

Clare returns to one of her beads. “It was my niece who said, ‘You know I think you need a shrink.’ I was really surprised when she first said it, but then later that night, I thought, ‘My God, I think she’s right.’ So that’s what got me here, sort of. Besides,” she adds with a mischievous look, “I hear your husband is good with people, so I figured some of you must have rubbed off on him!” I am amused because most people would have reversed that description.

“I’d like to journey with you and see the world through your eyes,” I tell her.

“Well,” she laughs, “I’m not so sure about the wisdom of that!”

“Well, then, what about the person behind the eye’s lenses?”

“Touché,” Clare answers.

“How much can you see now and how do you need the light adjusted in the room?”

“I can see about at arm’s length but things generally look like a white sheet in front of my eyes.”

Together, we arrange our space so that her chair is closer to me and away from the glare of the lights from the south window. I understand that today we will be relying primarily on tactile and auditory modes of learning since we will not access through the usual visual bonding.

“From what you’ve just told me, I guess we can say right off that you are a survivor because you are taking responsibility for your life by coming here,” I tell Clare.

“That’s pretty clever, that way of wording it.”

“Well, what would you call it? How would you name it?”

“Add scared. Maybe stubborn. A realist.”

“Well, scared, stubborn, realist, I think your words can easily sit side by side with mine. What do you think?”

“I’m willing to name it that for now.” Resisting a little, but willing to move ahead.

“Well, everything here is subject to change, but we can start with this working hypothesis and see if it’s useful to us.”

The mechanical timer interrupts us. The two hours have come and gone in an instant. We both feel the urgency of getting to know each other better and of doing as much as we can together before her next bone scan report. We agree that she will come in twice a week. We have a brief discussion of the economics of her therapy, and we negotiate a fee that she feels is fair to herself and her religious community.

And so begins our journey together.

***********

Today, the snow is so deep I can’t go out to the bird feeder beyond the Glass Room. No mountains. The stairs and the deck are all gone. Even a groundhog would have difficulty finding a way around the backyard. At the lakefront, there is no shoreline today, no hint of water or the life below. The Ethan Allen tour boat is frozen in for the winter.

Over time, I learn that as a “Mercy” Clare comes from a long tradition of female autonomy, unattached to men, an “unhusbanded” woman, vowed to virginity and poverty. She lives with a tradition in which each woman’s privacy is preserved at the same time that there is an intense and deep community spirit. She lives with two other Mercies in an apartment in a working-class neighborhood, living her vows to work with the struggles and suffering of the poor. She also regularly practices her day-prayer, work, quiet conversation, study, and community purpose.

Like her namesake, Clare of Assisi, the thirteenth century founding mother of Poor Clares, she participates in vows of chastity and voluntary poverty. And, like her predecessor, she practices the reciprocity of living out her life in the larger community, amongst the poor, sharing and understanding their lives.

In this session, I nudge the narrative forward. “What do you think draws people to you?” I ask her. Clare pauses for a while, holds her head down as if in prayer.

“I would say my ability to communicate well. My openness. My overall knowledge about things. My sense of fairness and justice.”

“Does all of that carry into your political work as well?”

In the manner of a true Socratic student, she responds, “Is there a difference between the two?”

She sits quietly for a moment. “I’ve thought about my beginning goals. As I said the first time I came, I need to develop the inner resources to deal with whatever is ahead for me and, as part of this, I need someone to journey with me. Then, too, I need to be ready, or maybe I should say I need to find some inner peace—I’m not sure what resources I will need—and then what do I do with the rest of my life? My life feels so interrupted, and time feels so fractured now.”

She sighs, and her shoulders drop. “I need a change in job. I did work in campus ministry with undergraduate students at the university, and I have been active in helping women to integrate their lives into religious community life, but now, here I am stuck.”

“Can we back up? What do you mean ‘not sure’?”

She pauses and searches within herself. “There are spaces, gaps, unknowns, places I can’t name yet—and also some gaps in my knowledge. I’m in so much turmoil about this. It’s such a struggle. I like to be independent. Having to ask for help doesn’t come easily for me. Yet, I know I have my community. I need someone I can speak with, where I won’t have to re-explain or reinvent myself and where I won’t have to worry about taking care of everyone else’s reactions to my diagnosis.”

“A climate where you feel understood? For who you are and what you stand for? For what you believe in?”

“Yes, without having to explain myself again.”

“Whom have you done this with before?” I ask Clare.

“Well, myself and my community.”

“Has that been a struggle?”

“Very much so, but I wouldn’t trade it for anything,” she admits.

“What is the ‘it’ here? Do you mean the experience and the process with your community? Your feminist consciousness as a woman religious?”

“Yes, but some of it has been very painful, especially with the patriarchal hierarchy and all the politics of power and control. It’s been mind-boggling. A few of us have been on this journey together and supported each other. These were hard times. Some women left the community.”

“Who has been in this struggle with you?”

“Well, Joyce, Marlene, Lucille, and Jan are still here.”

“I think I understand part of what you are saying because I have been going through my own process too. The Jewish religion has no historical tradition for women contemplatives, women who live, work, and pray together—although this is changing now.”

“Well, here I am!” she laughs. “Try me!”

“Thanks! So the old struggles are intermingled with this new struggle, having a diagnosis of cancer and it feels exhausting? Is that too strong a statement?”

“Well, I wouldn’t have said it that way, but that’s it, I guess,” Clare responds.

“I know. I went a little beyond what you said, to what I felt you said.”

“How do you feel that?”

“I think I hear the sounds in your silences,” I explain.

“That sounds mystical.”

“It sounds it, but it may be quite scientific. Let’s save this ‘mystical’ part for another day, if it’s okay with you.”

“Sure, but I won’t let you forget it.”

“I’m not trying to dodge it, but I want to stay with hearing your needs and goals and not go on a side journey for now.”

Again the mechanical timer, of ordinary time, goes off.

An Existential Dilemma

Our work continues with an urgency today. Clare continues trying to understand and explain her existential dilemma.

“I do not understand why God has given me more problems. Wasn’t my vision enough? Why is this happening? I thought the glaucoma and loss of eyesight was the big marker that I was being tested about. I feel that I am being tested all over again. I just don’t understand. How much can I take?”

“Are you trying to find the meaning to all of this? Or is it more about why me?”

Stubbornly, and with irritation, she digs in and blocks my intervention. “I—don’t—know—which.” Silence.

My response is out of sync. Too linear. I have lost her singular cadence. I must pull back.

I try again. “Let me try this, Clare.” She is patient with me. “Would it be something like this? Just when I thought I was starting something new, something to give me a new direction, I found that I have no plan, no vision, everything is blocked and fixed.”

“Yes, that’s it and it’s frightening,” Clare validates my understanding.

“Well, the first step is the naming of it, so that I can try to be in your reality.”

“I know. I understand,” she responds. We are in tune with each other again.

We sit in an Attuned Silence and then move forward together. Clare has invited me into her life. What can be more sacred? Will I be adequate to the task?

She has had a lifetime of experience that not many 40-year-old women have had. A life of faith burnished with prayer. What can I possibly offer this dispirited Sister? This woman who believes that the sacred life is not only in the dark recesses of the church pew, or in the robes of the priests hearing confession, but is everywhere in community, omnipresent in each of us?

Where can I bring her that she has not already been in prayer and on her many spiritual retreats? If the end point of our work may be death, how will we measure a successful outcome of our work? If her health cannot be measured in terms of longevity, how shall we define good heath and healing? What is it that we are healing here? And is it only Clare?

At the same time that I experience the enormity of what she is dealing with, I must prepare myself to move forward with her. This evening I sit home reading, listening to tapes and pulling from within myself whatever concepts, images, and new knowledge might be of help to us both as we move forward together. God is especially welcomed in tonight.

Again I ask myself, what can I offer this contemplative woman committed to peace and social justice? A woman who has sitting side by side on her night table the Bible with its mysterious wisdom and a Kübler-Ross tape on the stages of grieving and dying? I turn to Jewish mysticism, Buddhism, the shamanic healing traditions, and the ancient sacred traditions of healing through music. After all, I am not the first healer in search of a vision. And I wonder what would Hildegard of Bingen do? Or Clare of Assisi, or Teresa of Avila? Three women I have been researching for Clare’s story.

***************

My intent here, as with Astra and Nancy, is to enlarge and expand the knowledge space within which we will work. It is not only a knowledge space, but a circle of space that holds the tone, color, nuance, and tempo of her spoken life story. It is the creation of a shared reality, when and if Clare chooses to join that place and engage with me in it. A space we can labor, play, and pray in together.

At our next session, I have some old and some new teachings on my mind. I start our dialogue with the results of my homework.

![]() “Clare, I was reading last night that many peoples believe that human beings have more than one soul and that the souls can leave the body and wander around. The basic idea is that a person is not bounded inside the body. In one culture there is the soul which wanders and represents the person’s consciousness or personality, and there is the soul which stays behind to keep the body’s metabolism functioning. If the first of these souls does not return, the second will not long survive without it.

“Clare, I was reading last night that many peoples believe that human beings have more than one soul and that the souls can leave the body and wander around. The basic idea is that a person is not bounded inside the body. In one culture there is the soul which wanders and represents the person’s consciousness or personality, and there is the soul which stays behind to keep the body’s metabolism functioning. If the first of these souls does not return, the second will not long survive without it.

“And in the Inuit culture, people believe in the idea of a third soul, representing the person’s name, which is transmitted from one living holder to the next.”

“Are you trying to tell me something?”

I smile. “Only if the story means something to you, or is useful to you.”

I continue. “I also read that the Inuit people of Alaska believed that uttering a name created a mental reality. Objects and their names were equally important. A person’s name was part of her soul in that it symbolized her social existence and her relationship to the environment. It could also represent a person’s essence, what she would pass on to another person after death, in ancient Rome….”

Clare picks up the theme with a memory of her own. “You know, I remember a quiet summer morning in June when my mother brought me to the convent to ask for a miracle. An older Sister spoke with me.

“‘What is your name, child?’ she asked me.

“My name is Clare,” I said.

“You have a beautiful name, child. Did you know it means ‘light’,” she asked me.

“The light that this Sister gave me has always traveled with me,” Clare reflects.

I join her name story with my name story. I tell her that, during the last days of writing my dissertation, I received a letter from my middle child, my daughter, with the following story from Sophie Drinker’s Music and Women: (1948)

“…we find Judith, with courage and craft, seducing and slaying Holofernes, captain of the invading Assyrians. On her return, and after the defeat of the enemy, all the women of Israel, in gratitude and thanksgiving, ran together to see Judith and bless her, and made a dance among them for her…and she went before all the people in the dance, leading all the women: and all the men of Israel followed in their armour with garlands, and with songs in their mouths…And Judith said, ‘Begin unto my God with timbrels, sing unto my Lord with cymbals: tune unto him a new psalm: exalt him and call upon his name.’”

“This story about my name has been a source of strength for me and combines a number of my own qualities.”

I continue with this general theme because I see that it is energizing us and moving the narrative forward.

“Clare, I have been thinking a great deal about wisdom. What is it? How do we acquire it? Did you know that in the shamanic traditions of healing, special powers are often expressed in terms of special sight? There has always been this idea that wisdom involves some kind of second or inner sight. In a number of cultures there has always been an association with blindness and having special gifts such as the gift of music or poetry.

“In the Inuit culture, words of songs are part of the environment, like snow, bones, or skin. They have a functional property that can be wrapped, carved, or put together just like the material of any other craft.”

I read an Inuit song to Clare from a book:

I put some words together

I made a little song.

I took it home one evening

mysteriously wrapped…

We sit now in a more inclusive and richer silence. The silence of new possibilities.

“I really mourn the age at which this cancer has been diagnosed. I feel I am much too young.…

![]() Click here for more on Clare of Assisi

Click here for more on Clare of Assisi

************

I see with each visit that Clare has a practiced discipline of assessing her immediate environment. It is so subtle that I learn to ‘see’ as she gives me new information about the raw data of her life. Then my own attunement to the subtleties of her moving body improves. When she lifts a teacup to drink, I see her fingers glide slightly over the rim of the cup and into it. When she goes for a tissue on the little table, she uses her previously assessed calculations and knows the exact space between her body and the blue tissue box.

Later when we hug at the beginning of or after a session, or downtown on the street, I do not feel her measuring anything, but rather we experience a direct body knowing of each other. The sensation is akin to my own cellobodyknowing.

At the next session, Clare tells me, “You know those ideas of the Inuits and the additional souls. That part. I found it very enlarging. I had more images to play around with, more possibilities to consider. I enlarged the parameters of my world, but with my own Christianity still at the core.”

“I understand.” Good. I have received positive feedback about the value of my interventions on her core belief.

From early on in our therapeutic relationship, Clare and I worked almost immediately and with tenacity from that place of Inner Light that Clare required of me.

“The way I see it, you want to give spirit to what is already there,” I say to Clare.

“Well, I don’t know that for sure. I’m not sure what is there and that’s what frightens me.”

“I remember an old Talmudic saying, ‘Go to the mountaintop and cry for a vision.’ How lost we all are without a vision and someone to take the journey with us. I want you to know that I can take the journey with you. You don’t have to be alone. And you know you’re in the right place. Do you see Athena over there, the Goddess of Wisdom? Did you know that she supposedly had the ability to cure eye diseases? And I think I read somewhere that Saint Clare cured eye diseases!”

Clare smiles and our mood slips into the playful.

“And in the other room there’s Hildegard’s books and music, Teresa’s instructions in personal prayer and Clare’s Rules for how to live in a community together. And then there’s Kassia.”

“Who’s Kassia?” she asks urgently.

Aha, I have aroused her interest. Good, but don’t forget the others. “She was a major composer and poet from the Medieval period. She wrote Byzantine sacred poems and chants. She was also involved in the secular-political life of her time, but she decided to lead a monastic life. She wrote a liturgical piece called ‘The Fallen Woman,’ which is supposed to be autobiographical. Oops. I have a tendency to get carried away with these wonderful women….”

“No. I love it.”

She reinforces my desire to tell a story, and I continue.

“By the way, you remind me somewhat of what I’ve read about Teresa. She was a woman with a healthy intellect, a good imagination and humor, and a practical wisdom. And she loved to write, and she had her struggles with her health as well. She couldn’t walk for two years. I think she was in her 40’s when she said that it took twenty years of a painful struggle before she could finally get a Jesuit priest to validate her visions.”

“But now we know better about who to get validation from, don’t we?” she quips.

“You know, every morning I start the day with a cup of coffee and I speak with God. It is a very quiet time, a cleansing time, a state I love,” Clare tells me.

The tone of her voice, the sudden slowed-down tempo, the quality of movement inward, and her conversation with God bring me into one of my own altered states of consciousness, and an early childhood memory comes to me.

![]() It is a very hot summer day in Greenwich Village. The tar on the sidewalks between the cement cracks feels soft and gummy on the soles of my new white shoes. My mother has taken me beyond the borders of the familiar fruit and vegetable push-carts of Bleecker Street. We walk along Sixth Avenue close to Eighth Street until we get to the smaller, more distant church farther up the avenue. Going from the light to the darkness is blinding. The interior of the church is cool, mysterious, safe, silent. My mother takes me down the center aisle past the holy water. Soft reds, beiges, dark greens, and blue forms emerge from the darkness. Suddenly, my father’s voice overtakes me: “Don’t touch the water. Don’t look at the statues. Don’t kneel down. Remember, you’re Jewish!” But I like the closeness here with my mother and the darkness and the mystery….

It is a very hot summer day in Greenwich Village. The tar on the sidewalks between the cement cracks feels soft and gummy on the soles of my new white shoes. My mother has taken me beyond the borders of the familiar fruit and vegetable push-carts of Bleecker Street. We walk along Sixth Avenue close to Eighth Street until we get to the smaller, more distant church farther up the avenue. Going from the light to the darkness is blinding. The interior of the church is cool, mysterious, safe, silent. My mother takes me down the center aisle past the holy water. Soft reds, beiges, dark greens, and blue forms emerge from the darkness. Suddenly, my father’s voice overtakes me: “Don’t touch the water. Don’t look at the statues. Don’t kneel down. Remember, you’re Jewish!” But I like the closeness here with my mother and the darkness and the mystery….

Clare’s voice breaks through my reverie. “The big question for me has been how do I keep my reverence for our own traditions and the sacred in my life that goes beyond patriarchy? How do I recreate my life and find new paradigms for expression from some of the dogmatic ritual?”

“No small task.”

“I really mourn the age at which this cancer is diagnosed. I feel I am much too young.”

“I understand. You know St. Teresa was your age when she started her order at a time when only men could do this and then only with approval from the Pope.”

“I guess I’m in good company!”

“Maybe we can follow Teresa’s path. By the way, Theresa was my mother’s name.

The woman who is legally blind says to me, “Yes, what I need is to see more deeply and with greater clarity.”

************

Over time I learn that Clare has an undergraduate degree in English, cum laude, and a Master’s degree in Religious Studies. She has been an elementary school teacher, a religious educator, a spiritual counselor, a Director of Novices, and a member of the Formation Team working with women coming into religious life. She has been active both in her religious community and in the larger community in peace and justice work, and she is a member of the local Disabilities Council.

Clare and I started on different paths. I, a musician, a nurse, a wife, a mother of three, later a psychologist and educator. Clare chose a different way, giving up the reproduction of family life and choosing a communal life instead.

Both of us have been profoundly affected by the Civil Rights movement and the Women’s movement of the late sixties. During my three pregnancies, I raged as I watched the McCarthy hearings in Washington D.C., saw the bus boycotts in Montgomery, Alabama, and prayed for Rosa Parks’ safety as she took her rightful seat on the bus. In October 1962, as I made breakfast for my three young children, and sent them off to school, Pope John XXII convened the Second Vatican Council and brought new hope and new possibilities to Clare and her community. By 1966, when my children were 11, 10, and 8, Clare and many of the Sisters had removed their restricting religious habits.

In the early days of our growing feminist consciousness, both Clare and I have had to work ourselves out of the various stories of Genesis:

To the woman he said ‘I will multiply your pains in childbearing…Your yearning shall be for your husband, yet he will lord it over you.’ To the man he said, ‘Because you listened to the voice of your wife and ate from the tree of which I had forbidden you to eat, Accursed be the soil because of you. With suffering shall you get your food from it every day of your life…With sweat on your brow shall you eat your bread, until you return to the soil, as you were taken from it. For dust you are and to dust you shall return.’

(Genesis 3:16-19, Jerusalem Bible)

We struggle with our two traditions in which God is written about in patriarchal language and imagery. Clare has a wonderful memory and quotes a passage to me from Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion:

“God the Father loves you, and if you join the brotherhood and fellowship of all Christians you will become sons of God and brothers of Christ, who dies for all men.”

“Did you know there is an old prayer in Judaism, ‘Thank you God that I am not a woman’?” I ask Clare.

“No, but I’m sure you’ve changed that in some way.”

“Yes, I prefer this version:

‘Baruch atah Adonai, elohainu melech ha-olam, she-asani ishah.’

Blessed are You, Adonai our God, Ruler of the world, who has made me a woman.”

My own genetic memory as an Italian Jew joins my internal narrative. Clare may not yet know at this point in our work, nor perhaps did Teresa, that Teresa’s paternal grandfather was a converso, a person of the Jewish faith who, during the Inquisition, converted to Christianity under pressure from the Spanish courts and the Catholic Church. Spain at that time had an obsession with pure blood lines and pure race. Many of these conversos continued to secretly practice Judaism in their homes, an extremely dangerous activity. Jews were required to wear special clothing which marked them as Jews. Some Spanish Jews fled to Italy.

We discover that our literary histories merge as well. During the same period of history, we both read Mary Daly, Rosemarie Reuther, Charlene Spretnak, and Judith Plaskow.

Political analysis, a requirement of any democracy; the call to contemplation, reflection, and social action, a requirement of any feminist theology; and an egalitarian dialogue, a requirement of any feminist therapy, sit side by side now, strengthening us in our work together.

The Value of Therapy

In her own way, Clare has a habit at the end of each session that keeps me in a state of anticipation. She says, “Well, next time I want to talk about Peter and my early relationship with him,” or “When we were young and 18, in our community, we developed some physical attachments with each other. Who else was there to relate to in the convent?” or “The next time I see you, I’ll bring in another one of my favorite tapes.” Or “He invited me to dinner but who wants to eat with a bunch of priests?” or “Did you know that I have been dreaming circles and spirals?” or “Next time I want to tell you about Marlene. We both believe in ministry in reverse, what we can learn from people, not the reverse.” The storyteller’s daughter has her inquisitive therapist hooked!

Surprisingly, early on in our work, Clare challenges me to give her a reason for staying with her therapy.

“Isn’t therapy a very self-centered thing?” she asks. “I believe in a community of people. I don’t think you can talk about an individual character, a core self, without a context of time and place.”

“Go on,” I urge her.

“Well, it feels to me that therapy is a kind of self-aggrandizement. I mean, aren’t we engaged in a selfish act here that only a few of us can really afford? Isn’t this a really self-centered thing I am doing here?”

“I’d like to answer you on a few levels,” I respond. “First of all, it is not uncommon for a woman to ask this at some point in her therapy. You get restless for change. Then there is this whole issue of entitlement to this time and life space. Am I being selfish? Shouldn’t I be taking care of others first? I think this is a real women’s issue about self-entitlement, being deserving of the time and services for ourselves.

“But just think about this. A therapist’s office is one of the few precious places where women come to talk about meaning in our lives. What does this all mean? How do I live out my human-ness? There are far too few places in the culture where a woman can find this kind of support and dialogue. On the other hand, I think you are really onto something about how we define the self. Our psychological theories are really limited. All the psychology maps I know of are too small. We are so much more complex than our theories. A long time ago there was a split between science and philosophy. Psychology went the science route and forgot about the human spirit. The field of transpersonal psychology is the only field where spiritual and psychological theories are combined.”

“Yes. We studied this science/philosophy split in our theology studies,” Clare reminds me.

“You know, you can say that we are talking about the individual woman, but your self is in your body, and—”

And so begins the education of her Jewish therapist. The question about whether she is entitled to time for this “self,” whether there is even a personal self worth attending to, whether she should align herself with the “privileged” who can afford therapy is much more complex than I realized. Clare’s analysis and understandings would not be found in the psychological textbooks on self theories that sit on my crowded book shelves.

“I need to explain some things to you about my history,” she begins. “It’s important for you to understand about what pre-Vatican II and ‘formation’ did to the psyche. We women who joined our community all came with our personal histories. We came in as idealists with a sense of religious commitment. In our Catholic working class tradition, there were few ways a woman could be in the world. We had a choice of married life and childbearing, or a religious profession. If you think about religious commitment as change, then there was the idea of a higher justice and meaning to what you give your life to. And back then, there were not many factory jobs and the pay was very low.

“Our parents were French-Canadian and not political. There were no books, no going to an analyst, but love and relationships were very strong. Both Marlene and I attended bilingual Catholic schools. We were first or second generation women who could continue our education. We never thought of getting a loan, and we didn’t feel we could pay off loans, and our families didn’t want debts they couldn’t pay off. So that’s where we were.”

Her story spirals out as she continues enlarging my understandings. “By joining the community, we had a life of both dedication and education. And this opened up new avenues of resources for many women, but it took us a much longer time to get an education, usually eight to ten years to get our degrees. A lot of our education came through Trinity College, which our order started. And there was a work ethic—a communal respect for communal space—and the idea was to develop a communal psyche in a highly systematic and structured way. There was no private psyche.

“In the sixties, I’m sure you know this, there was a lot of individual freedom in the larger world. For us, that was not true. While women in the larger world were into drugs and sex with their newfound freedom, we were a closed, disciplined, authoritarian, and hierarchical structure that encapsulated the individual. Our egos and self-centeredness were definitely stifled. So, while our contemporaries were developing their individuality and placing Self at the center, we helped to maintain the status quo. Our personal gifts were not developed. They were labeled community gifts. Humility and pride were taught. Humility became a context in formation so that individual striving was not valued. So there is this real internal struggle now for me.”

“Can we get back to the self for a minute? You know, there is an old Talmudic saying that saving one person is equal to saving the universe,” I tell Clare. “What do you think of this? Of course, I am not negating anything you have just taught me.”

“That’s beautiful.” She sits quietly, reflecting on this.

“What about this time saving yourself? There is a difference between being occupied with yourself and preoccupied with yourself. Why shouldn’t we be occupied with our thoughts, feelings, beliefs, ideas, and good questions? Why shouldn’t we attend to ourselves? In fact, if we don’t attend to this, we will be perennially preoccupied.”

“Again, it sounds so selfish,” Clare responds.

“When is it selfish or self-absorption and when is it self-love? Is self-love bad? Sinful?”

“Sinful, perhaps. Unfamiliar to me would be closer.”

“Unfamiliar? Is a focused prayer selfish, self-centered?”

“That’s about God.”

“Yes, but you’ve initiated it.”

“You know, Saint Teresa wrote beautifully about prayer.”

We sit now in a Challenging Silence.

![]() Click here for more on Teresa of Avila

Click here for more on Teresa of Avila

************

While we are at the convent, she shares with me a copy of her vows:

“Each sister formulates her own expression of commitment, but includes in it the following statement of profession:

‘I, Clare, in the presence of community vow and promise to God, chastity, poverty, obedience, and the service of the poor, sick, and ignorant, according to the Constitutions of the Institute of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas.’”

![]() The commitment reminds Clare of another community story, this time from the 1970s.

The commitment reminds Clare of another community story, this time from the 1970s.

“The early seventies was a period of great solidarity for all of us in our community. In 1973 or ‘74, there was a lot of discussion about whether the federal government would pay for abortion. Sister Elizabeth Candon of our community, who was then Secretary of Human Resources in Vermont, announced that if the federal government wouldn’t kick in for abortion, then state funds would be used. Well, this stand brought the whole abortion issue and reproductive choices to the national level. Our community held the ground with Elizabeth Candon. We all supported our Sister’s right to speak in the public forum. The local bishop threatened excommunication, but, you see, for our community, abortion was not seen as a morality issue but as an issue about poor women’s lives. Our community stuck by our Sister. This event meant a great deal to us.”

As she ends her reflections on the energy and solidarity that historical period required of her and her Sisters, she guides me into the chapel. Two other Sisters sit in prayer close by.

************

When you wear no religious habit, what are the outer signs of an inner life? Communal rituals with other women are some of these markers.

![]() Clare is interested in rituals of the outer life that are markers not only of an inner life but of a political one. She has recently organized a group called Sarah’s Circle to develop rituals meaningful to herself and other women both in and out of her community. They meet regularly to pray and support each other. She invites me to the group, and I attend when I am able.

Clare is interested in rituals of the outer life that are markers not only of an inner life but of a political one. She has recently organized a group called Sarah’s Circle to develop rituals meaningful to herself and other women both in and out of her community. They meet regularly to pray and support each other. She invites me to the group, and I attend when I am able.

I start the session today: “You know, I was thinking that both Jewish feminist theologians and Catholic feminist theologians try to uncover the lost stories of women through historiography. In Judaism, we honor oral traditions, for example, passed on from mother to daughter to granddaughter, and the creation of feminist myths and commentaries, and ritual invocations and connections with our ancestors. These are modes of remembering for us. This is what I experienced with you at Sarah’s Circle when we prayed together the other night and created our other ways.”

“Yes,” she says like a wise Shaman, “We have the same Vision.”

“And now I have this Vision that what we are doing here, you and I, is creating another kind of oral and written tradition. This therapeutic record we are creating together is another mode of remembering.”

We are both stunned by this simple revelation. We experience the companionship of two women who come from different religious backgrounds and different life styles. We have gone beyond both.

We create here another community of spiritual friends. We share a vision with the Beguines of the Middle Ages and the Chinese marriage resisters of the Sung Dynasty, of which Janice Raymond has written extensively. Like them, we have a woman-willed and woman-defined independence. We are not helper and helpee. We are now the companions of equals.

************

![]() I am almost late for today’s session. Betty and I have just returned from Carla’s Memorial Service at one of the local colleges. The shortness of life again tugs at me, as I prepare to work with Clare.

I am almost late for today’s session. Betty and I have just returned from Carla’s Memorial Service at one of the local colleges. The shortness of life again tugs at me, as I prepare to work with Clare.

A few years earlier during her second therapy session, Carla had asked me to make two promises. Today, I was able to keep the first, for she was sure that the college where she had taught would someday have a Memorial Service for her. She wanted me to be there. The second promise, I could not keep. Carla, who knew early on that she had a terminal illness, very much wanted me to tell her story. But her story is one of the stories that will not be told for now, for I believe that it would be discredited not only by her medical diagnosis, but by her ex-husband in my profession who had tried to discredit our work.

I turn to the work at hand, but it is Carla’s story so filled with tenacity and courage that sustains me today as I work with Clare.

Clare often sits in the outer room of my office with her “Walkwoman” and her packet of tapes in her pocket or on a table close by. Often when I greet Clare, I cannot tell whether she is listening to her music or praying unless I see the little black wire hanging down from her ears, for she has the same inner peace on her face with either activity.

Today she walks in saying, “You know, when I listen to music, I can almost see forever.”

“I have a Cris Williamson tape [Changer and the Changed] for you. It says what I want to say to you; the music does it better for me.” I put the tape into my large stereo with the volume up:

“Sometimes it take a rainy day just to let you know everything’s gonna be all right, all right.

I’ve been dreaming in the sun;

Won’t you wake me up someone?

I need a little peace of mind.

Wake me from this dream I’ve dreamed so many times;

I need a little peace of mind.

Oh I need a little peace of mind.

When you open up your life to living, all things come spilling on to you;

And you’re flowing like a river, the changer and the changed.

You got to spill some over, spill.”

Totally taken in by the words and music, we suddenly both jump up, embrace each other, and dance around the room, missing at best two measures of the music.

This day marks the beginning of many days when we dance and sing to music that either one of us has chosen. Hildegard, the medieval mystic, sits comfortably with Chris. All move into our space now and join us in healing.

![]() Click here for more on Hildegard of Bingen

Click here for more on Hildegard of Bingen

At the next session, Clare is uplifted.

“Last week after we danced, when I went home I remembered one of the Psalms: Psalm 30:3, 11, and 12,” Clare tells me.

O LORD, thou hast brought up my soul from the grave:

thou hast kept me alive,

that I should not go down to the pit.

Thou hast turned for me my mourning into dancing:

thou hast put off my sackcloth,

and girded me with gladness;

To the end that my glory

may sing praise to thee,

and not be silent.

O LORD my God,

I will give thanks unto thee for ever.

Then I add, “And I felt a little like Miriam leading the women with tambourines and dancing in thanksgiving after God separated the Red Sea!”

************

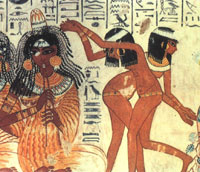

Tonight, at home, sitting alone in the darkness, I call forth all of the Muses. I summon up Miriam again and the other women percussionists and musicians from biblical Israel. In my mind’s eye I conjure up the ancient female iconography from the Egyptian tomb paintings with the inscriptions bearing the hieroglyphic names of women musicians.

Tonight, at home, sitting alone in the darkness, I call forth all of the Muses. I summon up Miriam again and the other women percussionists and musicians from biblical Israel. In my mind’s eye I conjure up the ancient female iconography from the Egyptian tomb paintings with the inscriptions bearing the hieroglyphic names of women musicians.

I do not want to imitate some of the older women’s autobiographies in which there is a tendency to find beauty even in pain and to transform rage into spiritual acceptance. Nor do I want to negate Clare’s pain. I begin to understand that Clare and I, through women’s music, are sometimes practicing a modern-day form of an ancient lament ritual, like the ones women performed in classical Greece and the Byzantine empire. Limited in many ways from communal and civic activities, these women were permitted the public voice of mourning. With intense expressions of grief and lamentation, they sang and chanted for the entire community of mourners. They did it so well, however, and were so powerful a voice, that they were eventually banned from this practice. Perhaps our joined lament, practiced here together, can restore some of what our sisters were robbed of. Sorrow and grieving give way to creativity, and our co-investigation process continues.

Joined Solitudes

As I work with Clare, I begin to notice that I eat more of my meals in silence. The simply-designed silver bracelet that I wear today also seems excessive to me.

Clare comes in, and after a hug, sits down and says softly, “You know what I experience here is a friendship. The strong image I have is of joined solitudes. I think there is great power in this, the coming together of two solitudes. That’s how I feel here working with you.”

“Thank you. And the same for me, too,” I tell her.

She continues, “You are a very spiritual person in the Jewish tradition. I find a tremendous respect for my Roman Catholicism here.” And then miraculously, uncannily, she anticipates a future ritual that we will have many years later. “I believe that together we have both gone beyond this. We have a new communion.”

![]() Today, it is my turn to bring in a tape I made for her from the book Les Guérillères, by Monique Wittig:

Today, it is my turn to bring in a tape I made for her from the book Les Guérillères, by Monique Wittig:

There was a time

when you were not a slave,

remember that.

You walked alone,

full of laughter,

you bathed bare-bellied.

You say you have lost

all recollection of it,

remember.

You say there are no words

to describe this time,

you say it does not exist.

But remember.

Make an effort to remember.

Or, failing that,

invent.

She loves it and keeps the tape for nighttime listening, next to Kübler-Ross and the Bible.

Clare has been reflecting on her life. “I’ve been thinking about what is my particular way. I need to be involved in the world. This has been isolating for me, lonely, frightening. A diagnosis of cancer separates you from the world. Everyone else is looking ahead, moving forward. The idea of life ending, a discrete period of time…” Her voice and thoughts drift off.

“That is our work here…finding Your Way.”

A blanket of inconclusive silence covers us. I lift the blanket to let more light in.

![]() “Did you know that Buddhism and quantum physics share the belief and knowledge that when you break down matter there is light and energy? It is said that, at death, when a monk is in a state of pure awareness, she has a rainbow body. I personally wouldn’t mind de-materializing into a rainbow of light some day. Would you?” I ask Clare. She nods, and chooses not to speak.

“Did you know that Buddhism and quantum physics share the belief and knowledge that when you break down matter there is light and energy? It is said that, at death, when a monk is in a state of pure awareness, she has a rainbow body. I personally wouldn’t mind de-materializing into a rainbow of light some day. Would you?” I ask Clare. She nods, and chooses not to speak.

“And did you know, there was a double-blind study in California. Of the four hundred patients of a cardiologist, half the patients were prayed for and half weren’t. The prayed-for ones did better in a number of measured lab tests. There is already scientific validation and information that prayer is healing.”

She pulls me up short. “I don’t need anyone to tell me that,” she says mischievously.

“That was naive of me. I forgot for a moment who I was talking with, but the question is what are the implications of this for your own healing?”

“I’m not sure yet.”

************

“Clare, last year I added some new bulbs in the garden.”

“What did you plant?”

“Crocuses, daffodils and tulips.”

“How long will they take to come up?”

“I expect that the crocuses will be ready in about six weeks and the others later.”

“That sounds wonderful.”

“Maybe we can celebrate an early spring together.”

“I could use that.”

I dig deep, not only to plant flower bulbs but to share with her some of my own existential dilemmas. “When I can, I like to walk to the old cemetery a few miles south of my house. Sometimes as I stand there, I wonder what the difference is between being above the ground or under the ground and if the answer really matters. I feel that I almost know the community of people in that old cemetery, as if…”

The Woman Religious interrupts me. “Well, yes, I think it does matter.”

“In what way?”

“Because in your time here, you can help end other people’s suffering. That’s the purpose of our life here. We are given life so we may help others.” The woman raised in the meaning of Christ’s life sits affirmed in her answer to me and remembers again, today, what she has always known.

************

“Well,” Clare sits down with a big sigh, “the bone scan is positive for a spread. I have a spread to my bones.”

For days, I have been preparing for the emotional weight of this moment and how to take on with her the burden of the report of the CAT scan. In this one moment, I must come up with the courage and solemnity of the High Priest during the High Holy Days of Yom Kippur, who has the responsibility to take on the sins and burdens for all of the people as God is approached in prayer.

“I am truly sorry, Clare. It must feel so unreal to you, no pain, no outward sign of any problem.”

“That’s it. I am so stunned. I feel numb.”

“And so out of control.”

“Totally. I really thought that my loss of vision was my burden from God, from which would come deeper understandings about other people’s suffering. I thought I was through with anything else, that this was the test of my life, and now this cancer. It feels so unfair. I’m too young.”

I think now of Teresa of Avilla who, in describing her experience of emotional pain, wrote, “I felt so much pain it was as if all of my bones were pulled asunder.” —Enduring Grace.

We sit for a while, two women caught in the Great Silence of Unfairness.

************

There are days when the rage, the sadness, the sense of unfairness and loss, and the isolation she feels overwhelm Clare.

“I live in a world of small print. I have to have everything read. That’s a loss of privacy and it makes me angry. I am afraid of spilling things in public, or a light may be too bright behind a person and I can’t see. My fear is that if I make such a big deal out of things, I will be totally paralyzed. I actually have more problems with my vision than I do with my cancer. I feel like an angry child who wants someone to take her pain away.”

“You know, Clare, Hildegard was touched with the gift of ‘visio’ from the age of three on. She had unusual and painful perceptions combined with a clairvoyance. She was able to see hidden things without losing consciousness or ordinary perception, and ‘brightness so great her soul trembled.’”

Between two sessions, Clare calls anxiously, not sure she can deal with the immensity of what she is facing. I know this is not an easy call for her because she is so proud about her independence.

“Can you tell me? How do you handle the idea of your own death?” she asks me.

The call is difficult for me because I feel her pain and I must dig into my own experiences with death and loss, to join her where she is.

“By living. That’s the only answer that makes any sense to me.”

I continue, “There is a story about a student confessing to the Zen teacher her fear of dying, what to do about dying if you’re not prepared for it. The teacher laughed and said, ‘Don’t worry about dying. We all succeed at that. It’s the living we’re not so successful at!’”

She presses me further. “What have your experiences with death been?”

![]() I dig for an early story. “Well, I grew up in a five-story family apartment house directly across from a funeral parlor. It was rare to have a day in which there was not a funeral or wake taking place. As a young child of 8 or 9, I would often hang out of the kitchen window in summer and watch the events across the street as I would watch any other event from my window. Death was an everyday event in my life—just like the routines of eating, roller skating, going to school, playing my cello. It was a fact of life. People would come and go in either the front or side door in black dresses, black suits, black ties and black face veils. In and around the community were purple-ribboned flower wreaths hanging on the doorway of a building where someone had died. I had not yet experienced a loss through death. It was actually a comforting sight, the public ritual, the beauty and scent of the flowers, the presence of people all doing the same thing. Observing these events offered a solace of sorts.”

I dig for an early story. “Well, I grew up in a five-story family apartment house directly across from a funeral parlor. It was rare to have a day in which there was not a funeral or wake taking place. As a young child of 8 or 9, I would often hang out of the kitchen window in summer and watch the events across the street as I would watch any other event from my window. Death was an everyday event in my life—just like the routines of eating, roller skating, going to school, playing my cello. It was a fact of life. People would come and go in either the front or side door in black dresses, black suits, black ties and black face veils. In and around the community were purple-ribboned flower wreaths hanging on the doorway of a building where someone had died. I had not yet experienced a loss through death. It was actually a comforting sight, the public ritual, the beauty and scent of the flowers, the presence of people all doing the same thing. Observing these events offered a solace of sorts.”

“What kind of solace?” she asks with her owl-like wisdom.

“Thanks, it’s a good question. Now that you ask, it gave some kind of comfort and order to my day.” But I carefully screen what I will and won’t tell her.

At the next session, Clare is still curious and wants more details. She leans forward with that attentive quality of the gifted woman I have come to know. “What kind of community was it?”

“Italian, Catholic working class. We were Italian Jews in a Catholic community.”

“That’s interesting.” She sits back now and stores the information.

We bond additionally now through our working class background. She makes no effort to offer me her own experiences with death, even though both her parents have died. And I do not take her questions to me as permission to question her. Still we move forward.

***************

I am not unfamiliar with suffering. I have worked with people in homes and hospitals whom I have fed and held one moment, and who were in death in the next. During the tragic and evil forties, I worked with hospitalized young children just freed from the concentration camps. Children who had blue tattooed numbers on their forearms, and other scars of human evil design far less visible. However, for a therapist, working through a woman’s diagnosis of cancer, this is a different kind of journey. It is often a longer journey; the roads sometimes less marked.

It is not that I fear death since I have been working with Clare, it is the anticipatory loss that I struggle with. The getting close and the letting go and struggling with other accumulated losses in my own life.

************

The adult woman who is so proud of her self-earned independence now finds herself pulled into a whirlpool of emotions. Clare has lost her hard-earned sense of normality, her sense of being like everyone else, as capable as everyone else. Her needs now appear to be too demanding, too obvious, too draining on others. Sediments of dependency issues lain dormant for so long at the bottom of a deep pool reappear and suck her downward.

She pushes me for answers. “How can you take doing this work? Have you worked with other women who have cancer?”

“Yes, women in my office, and men, women and children in hospitals.”

“Well, what is it for you, this experience?”

“Well, simply put, I have learned over the years that as I work with the intent to help or heal others, I myself am helped. I become more than I am and more than I imagined I could be.

“Why did you ask? Do you know?” I ask her.

“Well, sometimes I can’t bear myself.”

“The pain of it all? What do you mean?”

“I sometimes can’t bear myself,” she repeats.

“You mean like a burden. Would I experience you as a burden?”

“Yes. That’s it. I hate being dependent on anyone. My independence has always been so important to me.”

“So, how can I as a therapist bear a person who might be so dependent on me? Is that it?”

“Yes, but I don’t like admitting this to you.”

“I understand. The problem here is that we sit here stuck with two polarities, two words, dependent and independent, which limit a way we can think about this together. What about interdependent? The idea that as adult women we need each other? Is there a place for this word? Do you see what a new word does? The possibilities?”

She sits in silence, and then moves forward.

“I worked so hard with my vision problem to be like everyone else.”

“Sorry, but you aren’t! You are your own uniqueness, with your own mystery, and thank God for that. I am not trying to negate your thoughts and feelings here.”

She understands what I am trying to convey here. Much of her life has been in struggle with others. Now she is her own struggle, and she doesn’t like it at all.

She comes from a tradition of defiance and punishment, and she has the political stubbornness of Hildegard, who refused to dig up the body of a man whom she had buried on her convent grounds when the church authorities thought he was a non-believer. For this stance, Hildegard and her Sisters received an interdict from the hierarchy, a punishment by which the faithful are forbidden certain sacraments and prohibited from participation in certain sacred acts. Hildegard could no longer compose. She and her Sisters could not perform or engage in any liturgical music. Clare has a strong history to fall back on and I decide to bring Hildegard in with us again.

A Crisis of the Spirit

This week, Clare has another crisis of the spirit. She comes in tremendous pain and questions whether she herself isn’t the source of her own cancer. “Am I sick from my own misbehaviors? My own misdeeds? My own thoughts? The things I could have avoided? Did I produce this? Have I sinned in some way?”

“Well, I’m the wrong one to speak to about Christian sin or sin generally! I gave up the idea of blaming myself for many things a long time ago, and it was very curative for me.

“What you are saying is a classic example of blaming the victim. If you are thinking that your thoughts and lifestyle produced your cancer, then there are some relevant questions that you’ve left out of the equation. What about the toxic environment we all live in? And how do we sort out the chemical toxins from the ‘thought toxins’ from our education, from the pop culture that has diminished or limited our definitions of ourselves? And where do you place the facts of your inherited genetic makeup in your sin theory? Didn’t you tell me early on that you were committed to self-examinations of your breasts and that you did this, excuse the pun, religiously?” Clare nods. “And didn’t your doctor check you regularly? It occurs to me that you don’t know that some cancers of the breast are very fast growing, so fast that they are often not picked up by mammogram, by self-exam, or the doctor’s exams.

“In my own life, I don’t think much about sin but maybe more about forgiveness, forgiving myself and others, but it starts with forgiving oneself. In Judaism we focus more on communal sin. During the High Holy Days, we are reminded that any sins between people, we must straighten out with people, but the sins between yourself and God, you straighten out with God. I remember the exact day, it was just before Rosh Hashanah. I had gone on retreat alone and had stayed overnight at our remote cabin in the woods. After a whole day of prayer and reflection, I decided that my problem was focusing on my own sins or shortcomings. I realized that I needed to stop blaming myself, or focusing on everything I couldn’t change or giving attention to historical events in my life that were beyond my control. It was then that I gave up blaming myself. It was wonderfully freeing for me.”

“In my own life, I don’t think much about sin but maybe more about forgiveness, forgiving myself and others, but it starts with forgiving oneself. In Judaism we focus more on communal sin. During the High Holy Days, we are reminded that any sins between people, we must straighten out with people, but the sins between yourself and God, you straighten out with God. I remember the exact day, it was just before Rosh Hashanah. I had gone on retreat alone and had stayed overnight at our remote cabin in the woods. After a whole day of prayer and reflection, I decided that my problem was focusing on my own sins or shortcomings. I realized that I needed to stop blaming myself, or focusing on everything I couldn’t change or giving attention to historical events in my life that were beyond my control. It was then that I gave up blaming myself. It was wonderfully freeing for me.”

“How did it affect you, that decision?” Clare asks.

“Well, I left the cabin and went back home, and after I lit the Sabbath candles, I told my husband that we had to move so that I could return to school again after an eighteen-year absence. Up until then, I had put my children’s needs and my husband’s professional needs first, but that day I didn’t feel that I had to do any more penance.”

“Interesting,” she reflects.

“Did I go too far off for you?”

“Far from it.”

************

Clare comes in today feeling guilty, isolated, and confused.

“I’m getting into this guilt pattern, about what I’m not sure. And I feel I’m being perceived by others as a person who is always sick with something. I feel outside of things—isolated. I’m beginning to feel I’m buying into this script. I’ve begun to feel that’s who I am and I don’t like it.”

I question her further. “Are these feelings familiar to you? Does it feel like any other period of your life, this sense of being sick or different from others? Clare, are there any learned behaviors, old attitudes, old trapped ideas from the past that are limiting your movement forward? Behaviors or attitudes that have not been recently re-examined?”

Once she knows what I am looking for, she amazingly goes directly to the excavation site, and we are on a joint archaeological dig. “I do remember going through a stage in my life when I was ashamed of my father, that he was blind. I was 10 or 11 years old. I wouldn’t sit with him in church. I would go to another pew.”

“Why did the young child do this? What did you think would happen? Do you know?”

“Well, I didn’t want to feel different or strange, and I think maybe I thought I would get his blindness by association somehow.”

I support the young child. “Pretty typical thinking, Clare, for a young child.”

We sit in a long silence as she reflects with her left hand supporting her chin. Then she looks in my direction.

“What are you thinking?” I ask her.

“I wonder now whether I had the feeling that my own vision problems were a punishment. I had so many confused feelings at the time that they discovered the glaucoma.” Then, balancing herself, and giving herself the benefit of the doubt, she adds, “I guess I just feel really tired right now.”

“I can see why you would be with all of the chemotherapy and lab work going on, but I think you just did some important work. Allowing the memory in, painful as it seems, is hard work. There are often historical roots for our pain, but when we reexamine them, they lose some of their power and grip. Can you see that you reacted with the resources of a young child? Wanting to feel like your peers, not wanting to stand out. These are ordinary concerns of young children. Can you see that it would also bring out a fear, or pain of what being blind might feel like?”

As she sits reflecting on this, I hope that I have not pushed her too much.

“So you think that I might be projecting onto others what I felt as a child? That others might be seeing me as different and maybe wanting to stay away from me?”

I add to the narrative. “Trying to appear normal was a survival mode for you then, and much later when you had your own eye surgery, you continued in the classroom to try to appear like everyone else. But the problem is that—”

She interrupts me, “The problem is it won’t work now, right?”

“Well, as adults, I think we can pull from other resources, a repertoire of new possibilities.”

Measured linear time again interrupts our dig.

************

“I want to share something with you that has always been encouraging to me,” I begin. “Did you know that you have a new stomach lining every five days? Also, our fat cells are exchanged every three weeks. Our skin is new every five weeks. The liver takes about six weeks for new atoms to flow through it. Our skeleton is new every three months. I understand that ninety-eight percent of the total atoms in our bodies are replaced every year. However, the calcium in our bones takes a few years to replace itself.

“So you and I have many cells left to play with and many that are changing all the time, even with a diagnosis of cancer. It isn’t that we can necessarily change the pathology of the cancer cells but we have many other cells that sustain us. Let’s rely on these as well, imagine these as we plan for the future.”

She adds to the narrative. “I have heard of spontaneous remissions where there is a reversal of a tumor. Have you heard about this?”

“Yes.” I encourage her but with some reserve. “There are many cases that have been documented, but we are still far from understanding what this is all about. What is it that supports healing in these people? These cases don’t match our scientific paradigms so we don’t know where, as yet, to place them. Some healers believe that in certain stages of an illness the pathology is reversible, but in others it is not.”

We struggle together. We must search our way through this dilemma. Clare is stuck with a medical diagnosis foreign to her, now socially attached to her, which now defines her in a way she has never previously experienced. From her childhood, she knows struggle. However, that experience did not prepare her for the immensity of this new one. She sees death as an enemy of life. Death is her ultimate fear, death as the bitter end—the final tragedy.

The pain of this problem is evident today. Her normally smooth and connected legato voice has a short, detached staccato quality. Her words are short semi-quavers in length: “I feel that I have so little time...Time and a future have been taken away from me. I feel I have been robbed of my time… Forty is…so young. I expected to do so much more…and I have always had a meaningful vocation. Now, suddenly I am without work and direction.”

I must draw from the deep well of my own compassion. “I understand and share your grief. I feel that same grief with you about your time. You feel put aside, left behind, denied the infinite lifetime that others appear to have. I understand this. I, myself, would have the same reactions you are having, the same grieving, the same rage and anger, the same questioning of God’s mercy and justice if I had a diagnosis of cancer.

“But let’s think about this grief and how it happens. I think this grief has to do with two things. First about time: Whether we think of time as linear and one directional, moving forward from the past, toward a future which is finite, or whether we think of time as boundless and infinite. In the latter, every experience would be complete in the very moment of the experience.”

Clare and I are somewhat stuck here with a problem, for every culture requires that a person have a coherent thread running through a life story. In our culture a sense of a self through time is our most basic form of coherence. A narrative is structured around the assumption that a temporal sequence is a relevant dimension of understanding. We must have some connection with the past, present, and future. This is who I am. This is where I am. This is how I got this way. This is where I am going.

Clare’s life narrative feels like it has no place to go. She feels she is stuck and in pain in a Dead Space. Without a cultural future. Her cancer story places her outside the mainstream story.

I have so often asked the women I work with to be patient, to trust that time will make a positive difference in their lives. This will not work well for us however; it is not where the emphasis can be. Time will not change this diagnosis, and we are trapped in some unexamined concepts not only about time but about the diagnosis of cancer of the breast.

“Clare, we are all attached to life and most of us have an aversion to death. It is our ultimate fear. We all know we are going to die, but we don’t know when or how, so most of us don’t prepare. Perhaps it is impossible to prepare, but together, we must figure it all out. I know for sure that the way that you and I conceptualize life and death, health and illness, will make a difference. Whether we see health and illness as part of the whole of our lives, part of the same cycle, or whether we see health and illness, life and death, as opposite ends of a finite lifetime of some sort,” Not easy for me to say or a 40-year-old to hear.

“There are two ideas here. Let’s see, where am I with this? Oh, yes, I remember. It matters as we work together how we think about time, if we think about time as linear and one-directional and finite or if we think of our lifetime as infinite. In one, we would feel grief. In the other, every experience would be complete in the very moment of the experience. I don’t know if I have made myself as clear as I can be here. These are difficult concepts, and I struggle with you with all of this.”

Her left hand cups her chin, and her elbow is propped on the arm of her chair. She does not respond at first, but I know she is with me.

“I really need to reflect on this,” she sighs and disappears for a while in the inner sanctuary of her mind.