1098-1178

“Names from the margins of our historical awareness are rediscovered, illumined, shifted toward center.” —Symphonia, by Barbara Newman.

Thank God for the Benedictine nuns from Hildegard’s daughter house who were the first to undertake translating Hildegard’s work into German. Then in the 1960s her works were translated into English and that is how we now have Hildegard with us sitting in the inner or outer rooms. And thanks, too, to the all the students and scholars of medieval history and culture, musicologists and historians of science and religion, who bring us the timeless transcendence of Hildegard’s works.

Hildegard was one of the most important treasures of the Middle Ages. From 1098-1179 she lived in the Rhineland as a monastic in a cloister, obedient to the Benedictine Rule for 73 of her 81 years.

She came from a family of wealth and prestige, as did her later sisters Clare and Teresa. The tenth child in the family, she was dedicated at birth to the church, and at the age of 8 she was offered to God as a ‘tithe.’ She was sent to the abbess Jutta von Sponheim who led the convent at Disibodenberg. Jutta, six years older than Hildegard, was herself born into a wealthy and prominent family. It is of interest that Hildegard was later to write that she condemned using the monastery as an escape from illness, and objects to the forcible dedication of children to the religious live. (Vision:The Life and Music of Hildegard Von Bingen, p.9)

Jutta had chosen a life of religious seclusion near the recently founded St. Disabod monastery, the Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg. Hildegard received a rudimentary education from Jutta. She learned to read the Psalter in Latin.

From what I understand from my reading, instead of entering a convent, Jutta followed a more difficult path and became an anchoress. Anchors led an ascetic life, shut off from the world inside a small room, usually built adjacent to a church so that they could follow the services, with only a small window acting as their connection with the world. Food would be passed through this window and refuse taken out. Most of the time would be spent in prayer, contemplation, or solitary hand-working activities, like stitching and embroidering. Some reports seem to suggest that they may have had a servant with them as well. In later years, about a dozen girls from noble families who were attracted there by Jutta’s fame joined the cloistered community.

When Hildegard arrived, the existing monastery was fairly new and under construction (p.6, Barbara Newman, Voice of the Living Light). The anchorage was physically attached to the church of the Benedictine monastery so that the young Hildegard was exposed to musical religious services that were later the basis for her own musical compositions. It is not clear whether the women had their own chapel for singing the Divine Office or whether they participated with the men. They were dependent on the monks of St Disabod, and subordinate to the men and dependent on the monks not only for the services of a priest, but also for finances and administration.

Jutta was highly regarded at the monastery and practiced prayer, fasting, vigils, nakedness and cold; she tortured her body with a hairshirt and iron chain, which she only occasionally removed, and she refused meat for eight years in defiance of the abbot who urged moderation. It has been written that one day a week at least ,she recited the entire psalter, which in winter time she often said barefoot. These practices were not unusual in monasteries and convents, but not everyone practiced this. (p.6, Newman, Voice of the Living Light)

Apparently Jutta herself had prophetic powers. She was often able to predict a future event. She had a reputation as a healer and her fame made Disibod into a mecca for pilgrims. So Hildegard did receive another kind of education from Jutta! Jutta, in fragile health, died worn out and at the young age of 44.

At 15 Hildegard received her veil as a Benedictine nun.

When Jutta died in 1136, Hildegard was 38 and was then elected the new abbess of the Disibodenberg cloister, but she continued to live in her anchorage.

Hildegard tells us that she was touched with the gift of ‘visio’ from the age of three on and that she had unusual and painful perceptions combined with a clairvoyance. She was able to see hidden things without losing consciousness or ordinary perception, and “a brightness so great she soul trembled.”

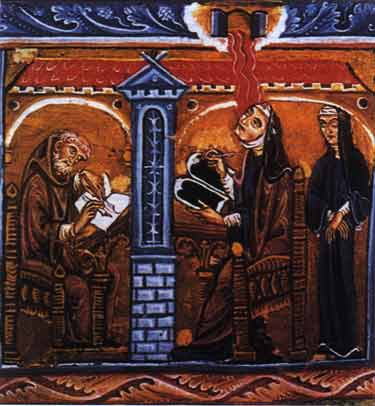

During all these years Hildegard confided of her visions only to Jutta and another monk, named Volmar, who was the provost at the cloister. He became her lifelong friend and secretary. Hildegard wrote down her visions herself and then Volmar served as copy editor.

In 1141, in her forty-third year, Hildegard had a vision that changed the course of her life. A vision of god gave her instant understanding of the meaning of the religious texts, and commanded her to write down everything she would observe in her visions. She had ‘a divine call’ that commanded her to tell and write what she saw and heard in her visions. Apparently,with much anxiety she began to record her visions that she had since early childhood. Her dramatic visions dictated by her were put in colored graphic form which we all can share now. (See Barbara Newman’s letter.)

“And it came to pass...when I was 42 years and 7 months old, that the heavens were opened and a blinding light of exceptional brilliance flowed through my entire brain. And so it kindled my whole heart and breast like a flame, not burning but warming...and suddenly I understood of the meaning of expositions of the books...”

Yet she was apparently overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy and hesitated to act.

“But although I heard and saw these things, because of doubt and low opinion of myself and because of diverse sayings of men, I refused for a long time a call to write, not out of stubbornness but out of humility, until weighed down by a scourge of god, I fell onto a bed of sickness.”

Without formal education in singing or music she began to compose. She had already been writing and composing in 1140 and in 1147-48. Once she started writing she wrote voluminously, and at a time when few women wrote, Hildegard produced major works of theology and visionary writings.

Hildegard wrote all of her music for Mass and the Divine Office at her monastery (p.12, Symphonia). A Monastic worship is ordered around the Divine Office, which consists of seven daily “hours” or services of common prayer plus the night service of matins....Each hour consists of varying proportions of psalmody, lessons from scripture and assorted texts of prayer and praise set to music-canticle, antiphons, responsories, and hymns. (p.13, Symphonia, Barbara Newman)

In 1147, with luck, support, some letter writing and a set of timely circumstances, she was able early on to receive official recognition for her writings and visions from the highest authority in the church. After this official recognition she was a celebrity. (p.4)

She was in her fifties, sick and in a period of great struggle. Hildegard must have felt that she had outgrown her physical and spiritual place—the double monastery. In one of her many rich visions she received the order to found a convent at a desolate old site where St. Rupert had lived. Many thought she was out of her mind.

After many difficulties and hardship with the monastery hierarchy (which did not want to lose the money and prestige her work had given them), she moved to the abbey at the Rupertsberg near Bingen in 1150, with eighteen nuns who joined her. It was rebuilt two years later. This move allowed her to be free from the male monastery and to bring her finances (nuns’ dowries and monies from her fame) to this new place. Hildegard was one of the first women to establish an autonomous convent.

During the 1150s she also had many correspondences with a wide cross section of people, and at about the same time she started her amazing writings on natural science and music.

She recorded her visions in three books. Her first, Scivias—May You Know the Way, took ten years to complete. It was based on 26 visions, with themes about creation, redemption, sanctifications. Seven years later, in 1158, another, The Book of Life’s Merits, and in 1173 she finished On The Activity of God. She was then 75.

In her 70s she characterized her visions as “a non spatial radiance that filled her visual field at all times.” A voice from heaven interpreted the forms to her in Latin. It was this voice that she maintained dictated her books and many letters. (p.3)

She described a celestial concert that she heard when the heavens were open to her which sounded like ‘a multitude singing in harmony.’

In 1165 she bought and restored a vacant monastery in Eibingen across the river from Bingen, on the other side of the Rhine, and started another convent. Between 1158 and 1169 she went on four preaching trips visiting monastic communities. In her later years, from 1158-60, it is remarkable that she traveled extensively in spite of her growing weakness. She traveled in order to preach, to reform monasteries, and to persuade priests and laymen to a Christian life.

Her remaining years were very productive. She wrote music and texts to her songs, mostly liturgical plainchant honoring saints and Virgin Mary for the holidays and feast days, and antiphons.

Hildegard produced poetry and music for more than 71 liturgical songs, a morality play, a compendium of healing arts, and a descriptive catalog of flora and fauna of the natural world. She used the curative powers of natural objects for healing, and wrote treatises about natural history and the medicinal uses of plants, animals, trees and stones.

In 1178 at 80 she had the now famous or infamous interdict which I have previously written about in Clare’s story. She writes the prelates of Mainz and challenges those who would stop the flow of music.

In her strong appeal to the prelates she protested the interdict, and spoke about her theology of music. She warns the prelates to “beware before you use an interdict to stop the mouth of any church of God’s singers...lest you be ensnared in your judgments by Satan, who lured men away from the celestial harmony and the delights of paradise.”According to Hildegard to silence the music of the church was to create an artificial separation between heaven and earth, to pull apart that which God had joined together.

When few women were accorded respect, she was consulted by and advised bishops, popes, and kings.

Hildegard’s life spanned the reigns of twelve popes, and four Holy Roman Emperors.

Hildegard died in 1179, at the Rupertsberg monastery, living all but the first eight of her eighty-one years as a cloistered Benedictine nun.

In 1233 Pope Gregory 1X began proceedings for Hildegard’s canonization. Among the witnesses were three of Hildegard’s nuns, who asserted that they had seen Hildegard illumined by the Holy Spirit as she walked through the Rupertsberg cloister, chanting one of her musical compositions. (From Vision)

After she died, her devotees felt that she should be venerated as a saint. She has not been formally canonized by the church, but Hildegard is considered a saint in Germany, and on her death’s date, she is observed in several German dioceses, especially around the junction of the Nahe and Ghan Rivers. (pp.5,6,14)

In 1979, at the celebration of the eight hundred years of her death, the pope John Paul II defined Hildegard von Bingen, one of the most remarkable women of the Middle Ages, as “the light of her people and of her time.” (p.26)

*************************

I encourage those you have been following these notes to read Hildegard’s Symphonia with introduction, translations and commentary by Barbara Newman from which I have liberally quoted. Her work will enrich your understandings of this woman’s many gifts and struggles and the time period in which she lived.

And several additional books:

Six Medieval Women, Andrea Hopkins, Barnes and Noble Books, 1997

Vision: The Life and Music of Hildegard of Bingen, by Jane Bobko, Barbara Newman and Matthew Fox.

Vision and Longings: Medieval Women Mystics, Monica Furlong, Shambala Press, 1997

Saint Hildegard of Bingen, Symphonia: A critical Edition of the Symphony of the Harmony of Celestial Revelations, Barbara Newman, Cornell University Press, 1998

Hildegard of Bingen: The Book of the Rewards of Life. Translated by Bruce W. Hozeski, Oxford University Press, 1994

![]()